Wonderlandscape

One of us has been re-reading Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll (aka Charles Dodgson) and we have discovered how relevant this 19th century children’s book is to anyone interested in 21st century landscapes.

We’ll tell you why we’ve been rediscovering Alice and the White Rabbit in a minute, but re-reading as an adult revealed many caricatures of modern situations. Take the Caucus-race: the Dodo (thought to be based on Charles Dodgson himself) marks out a race course, and places the participants here and there along it. Chaos ensues when runners set off or stop whenever they feel like it. How many business meetings or family discussions have you encountered, which feel just like that? The Dodo declares all to be winners and insists that Alice supply the prizes. She complies and finally presents herself with her own thimble. A classic representation of having a brilliant idea, only to have it adopted by someone else and presented back to you as their own wonderful work.

The trial of the Knave of Hearts reminds us of the Planning Inquiry which we recently endured (regular readers will be aware of this, see Qimby - Blog 167, and ‘How do I love thee’ - Blog 173). We have just had great news: the Queen of Hearts – no, no, the planning Inspector - has dismissed the developer’s appeal, to the delight of the local community group and, we hope, the local planning authority.

And of course we’ve all been caught ‘painting the roses’. Poor gardeners: ‘Two’ (of Clubs) explains that they have planted a white rose tree instead of a red one. Rather than be beheaded by the Queen of Hearts (no, definitely not the planning inspector) the gardeners are busily applying red paint to the offending flowers. It’s also very reminiscent of The Traitors. In this case, banishment plays out in Ardross Castle, located in a glorious Scottish highland valley, north west of Invergordon (below right).

By Anne Burgess, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=177648807

Our obsession with Alice’s visit to Wonderland-scape was actually sparked off by the National Trust. Our first introduction to visiting Trust properties at Christmas was PC (Pre Covid), when we enlivened a long drive with coffee, cake and Christmas at Greys Court (below) and, on the way back, at Prime Minister Disraeli’s home at Hughenden Manor. Both houses were pretty much decorated for a Christmas season appropriate to their history and inhabitants, and Hughenden had an excellent display of good old fashioned paper chains.

Things have moved on considerably since then. It’s Christmas 2025, and Standen – an Arts and Crafts property in West Sussex - was bristling with Christmas trees and messages to Father Christmas representing the family and staff who might have been in residence over the festive season. The decorations took their theme from the wish lists and expanded on them significantly!

Above: a map lover’s Christmas

Our only problem with Standen was those Christmas trees. Not because they are plastic (unfortunate of course but we can understand the convenience and re-use factors) but because they are obviously Nordmann firs (see image right, and our Christmas Day blog entitled ‘ Christmas Trees’). Even our plant identification app thought they were Abies Nordmanniana!

Surely the historically appropriate Christmas tree for a house of Standen’s vintage would have been a Norway Spruce? But I suspect we should blame the artificial tree manufacturers rather than the National Trust.

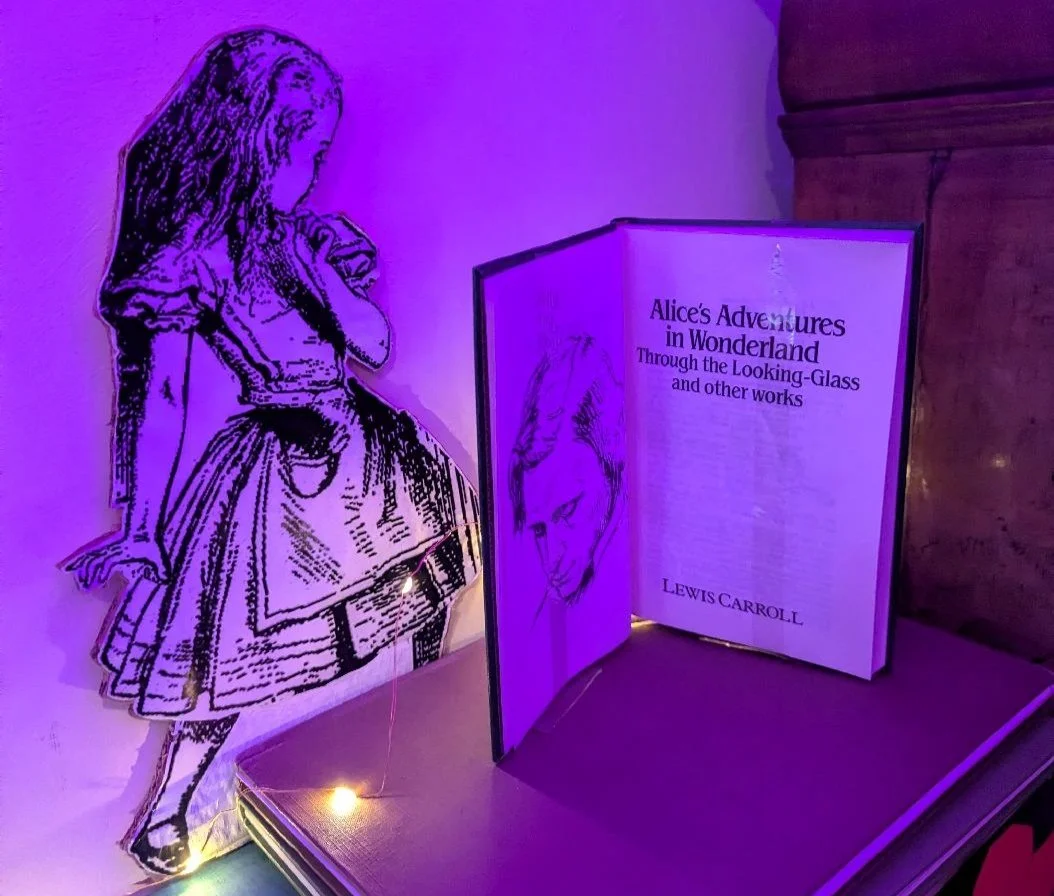

Going back to adventurous Alice in Wonderland, however, we discovered she had taken up residence in Polesden Lacey (right), the Edwardian makeover of a much older building, which became the Surrey home of society hostess Dame Margaret Greville.

We have visited Polesden Lacey many times so it was something of a shock to walk into an entrance hall stuffed, festooned and swagged (is that a word?) with a riot of artificial flowers which smacked of the tropics rather than the Home Counties. The Christmas tree (left) was a actually a pale example of the oversized and over colourful blooms which filled the space.

Of course we hadn’t done our homework but it didn’t take long to realise that Polesden Lacey’s interior had gone down a rabbit hole and had emerged in the garden of Lewis Carroll’s imagination. In our ‘eNotated’ version of ‘Alice in Wonderland’ the introduction reads: “Perhaps without truly intending to, Lewis Carroll peppered this children’s classic with death, mutilation, racism, politics and savagery while also dealing with anger, confusion, memory, logic, reason, women’s role, and insanity.” (eNotated by PamSowers – 2012). To be honest, I didn’t quite get all that when I read it as a child, but I did register fear, confusion, and a smattering of incredulity!

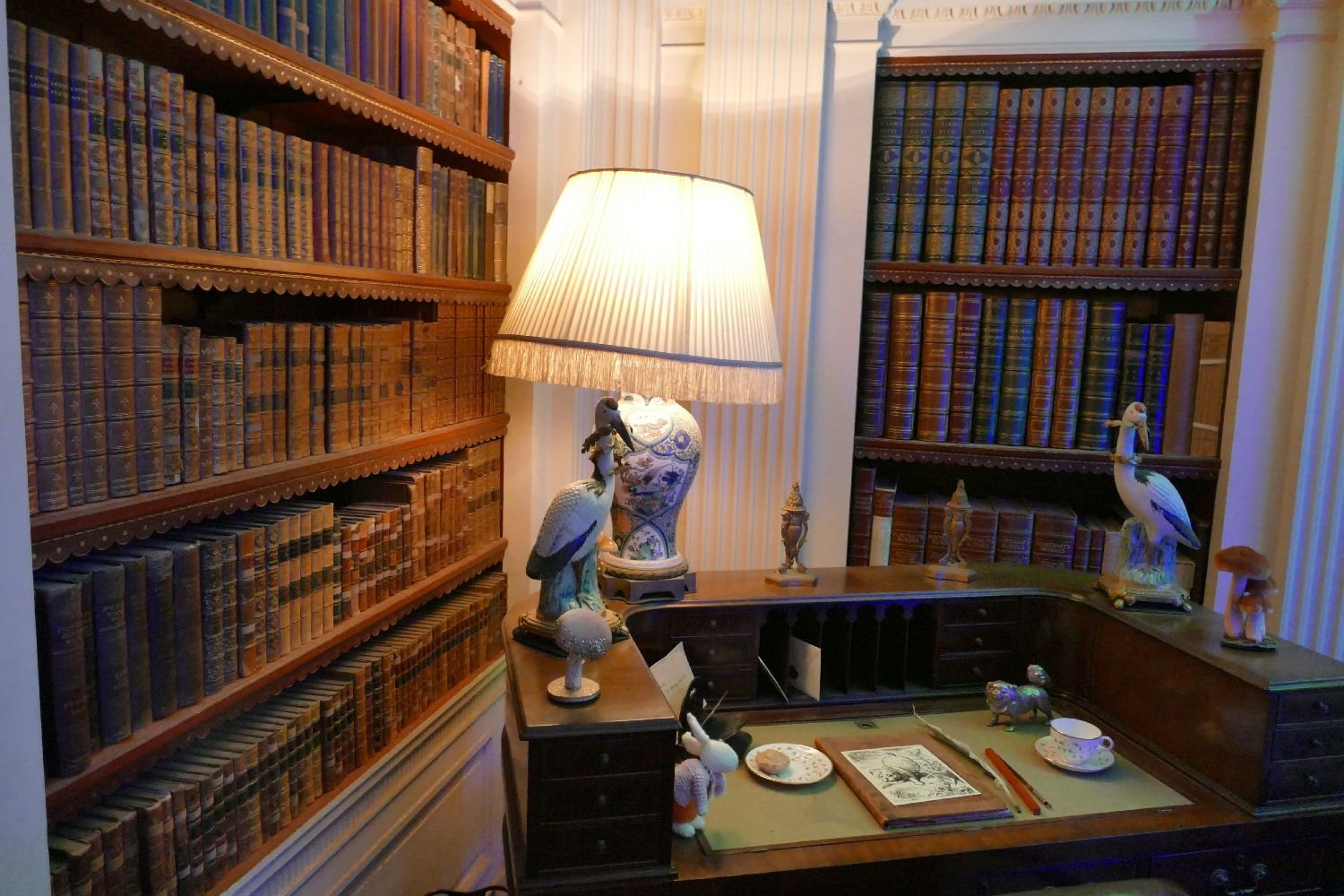

Once we had adjusted our mind set, we pressed on through the Wonderlandscape. We had to queue to get into the library but at least we weren’t forced to drink strange potions or nibble on dodgy biscuits. Entering the room at our normal height we looked around at the comfortable array of leather bound books and a writing desk of apparently unimpeachable character.

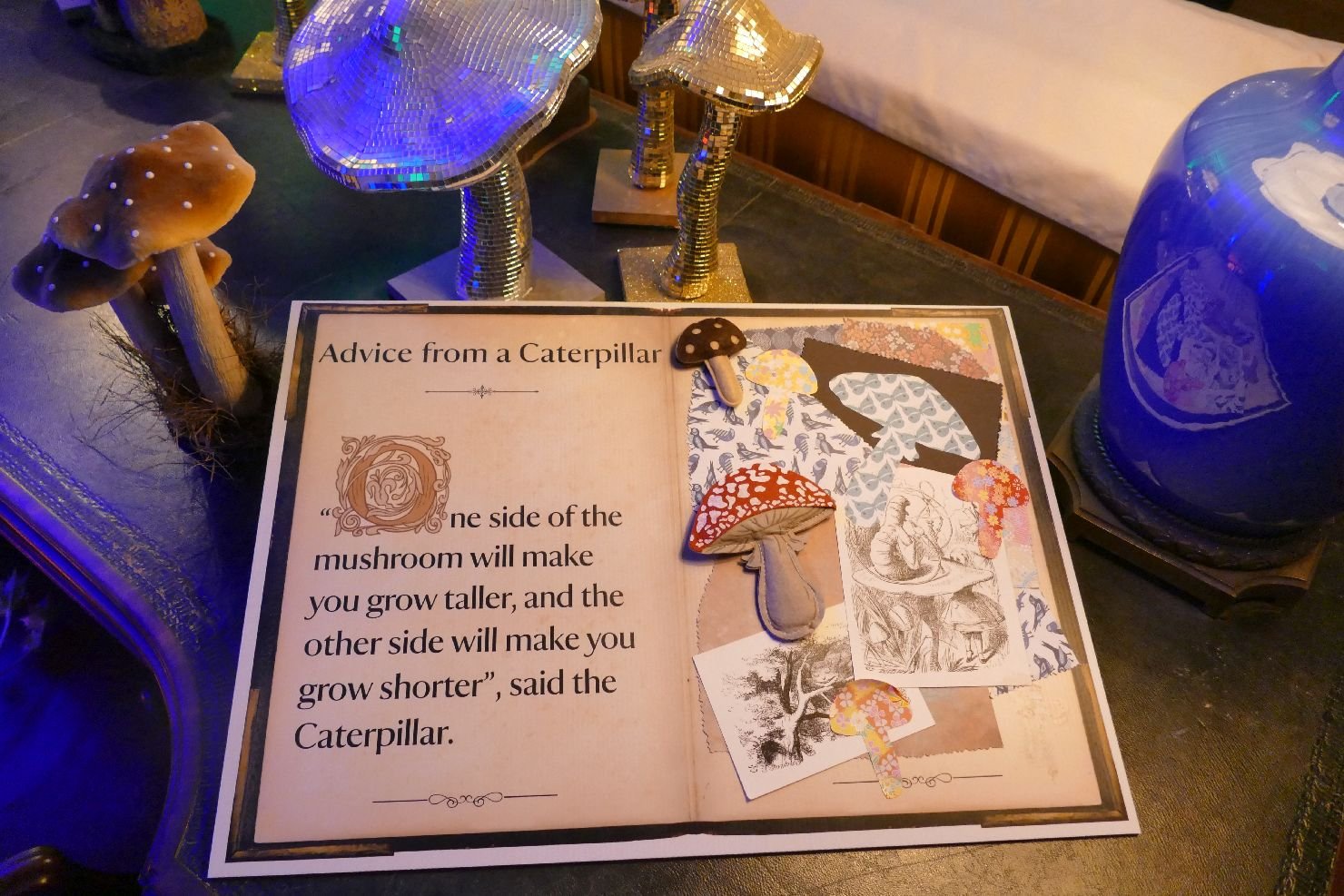

But look more closely dear reader: what Edwardian furniture would sport such strange objects as ceramic fungi and a small white rabbit? Suddenly a Cheshire cat appears and, yes, it’s ‘Behind You’, a worryingly psychedelic array of toadstools. The children seemed to love it. Although we suspected that the hookah smoking caterpillar was perched a little above their eyeline.

A flexible smoking insect was nothing compared with the Mad Hatter’s tea party and I don’t think either Lewis Carroll or his illustrator Sir John Tenniel had imagined such a colourful riot. We certainly didn’t when we read the book. To be honest, I think One of Us was more terrified by Tenniel’s grey, Victorian illustrations than by any aspect of the text.

It’s all there – croquet, chess, criminality (who stole the tarts?) but if the trial of the Knave of Hearts was reconstructed, I’m glad we missed it.

As we stumbled into another dimly-lit, potenial cave of horror, One of Us cried out, in joyous relief, ‘You’re Nothing but a pack of cards!’. We could so imagine Alice’s relief at finally taking control and waking up.

But we, the visitors, hadn’t woken quite yet. There was one last room where the designer had added a little bit of their own magic. There, tucked away in narrow corridor, was a ‘dry book wall’ looking like nothing so much as Welsh slate steps, leading Alice out of the rabbit hole and back to her sister on a Surrey river bank. Pure ‘wonderlandscaping’ wizardry.

Farewell to 2025

January 2025: the perfect post-Christmas colour schemes

February: ‘tenacious of purpose’

March: London

April: Hard won celebrations

May: Wild Life

June: Colours

July: remnants of an undemocratic but very stylish Rotten Borough (Gatton Park in Surrey)

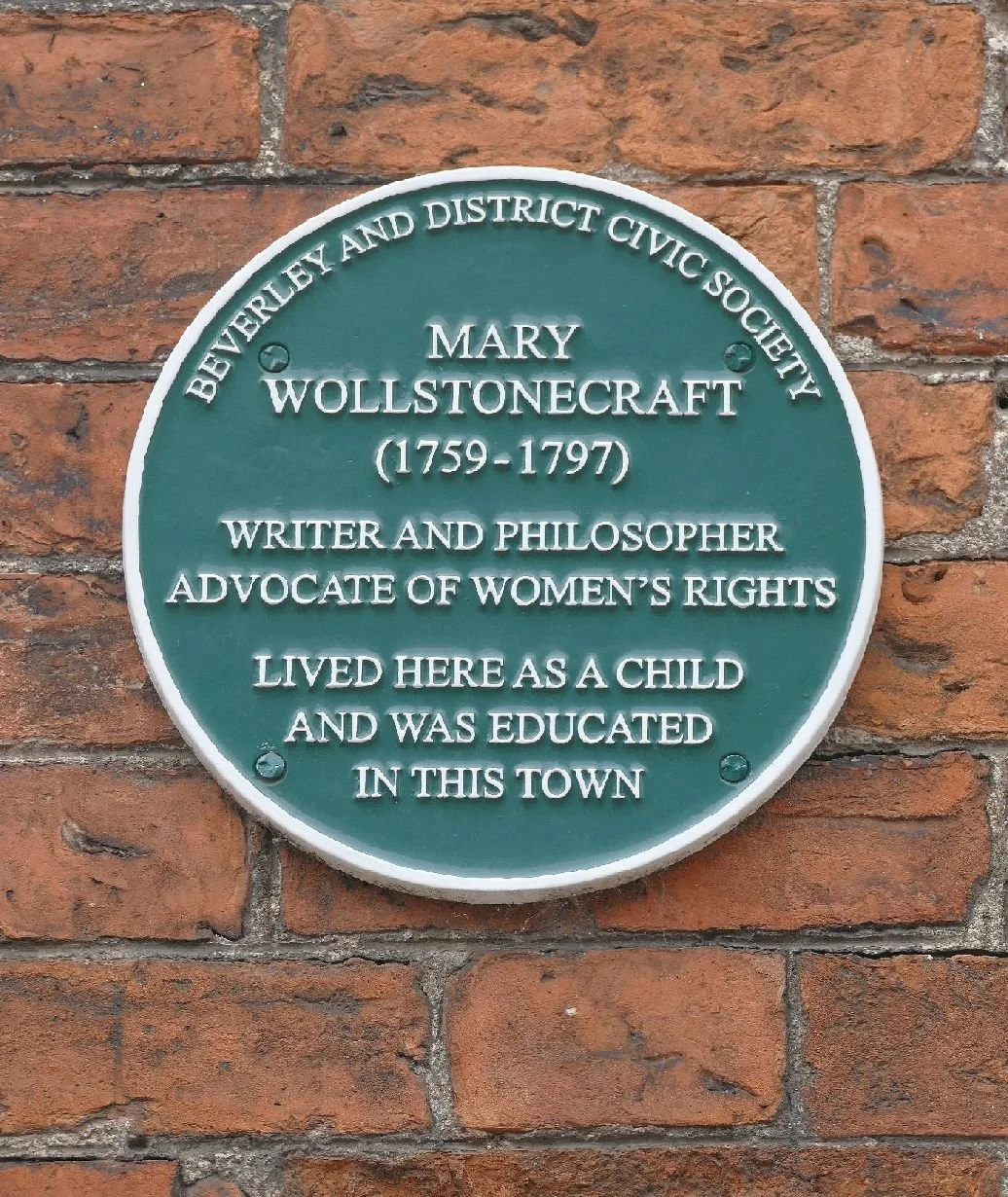

August: Women in Beverley, East Riding of Yorkshire

September: Stonehenge

October: County Durham

November: Quirky

December: Christmas celebrations

Best wishes to all for a very happy and healthy 2026.

Christmas Trees

How do you like your trees at Christmas?

When Terroir was little the tree which arrived in our living room every December was a Norway spruce (Picea abies). This is the same species of tree which the city of Oslo donates to London every year as a memorial to the welcome and support offered to the exiled King of Norway and his government, during the Second World War. Newcastle receives a Norway spruce from its twin city of Bergen, also to commemorate support and friendship provided during the war years.

So perhaps it is unsurprising that, for decades, the Norway spruce was the Christmas tree of choice in most British households. Actually, from memory, it was the only tree available and one of us can remember being shocked when other species began to be introduced. What? Break tradition with the Norwegian Spruce?

Above: a somewhat undernourished Norway Spruce, decorated to look like a maiden aunt and relegated to the Christmas garden

But we did and it’s now a Nordmann or Caucasian Fir (Abies Nordmanniana) (left) which provides the centre piece of our Christmas decorations. Glossy green and better suited to modern centrally heated homes, this native of eastern Turkey, Georgia and the Russian Caucasus holds its needles, tinsel and baubles with panache.

Are we being unfaithful to our British roots (pun intended)? How did non-native conifers become the symbol of a British Christmas? We can blame Prince Albert and Queen Victoria for starting that tradition, of course, although most of us have drawn the line at adopting the custom of opening our presents on Christmas Eve!

Our national tree is, of course, the mighty Oak and one can understand why this didn’t really catch on as the arboreal decoration of choice for a winter celebration, particularly for those of us who don’t live in baronial halls and palaces.

In out pre-Christmas travels, however, we did see many natives which would have made splendid outdoor Christmas trees. Let us celebrate these while we cover our non-native conifers in angels and stars. Here is a small collection of outdoor Christmas trees:

Above: our mighty English Oaks - determined to show their versatility by presenting themselves as pre decorated for Christmas but just missing that trad green and red theme!

These Christmas trees also come pre-decorated: with mistletoe (above left) and baubles (on a rather plain plane, above right)

Trees also come complete with back- or fore-grounds. These theatrical compositions are the perfect addition to your festive landscape. Above left: a valley landscape with train and, right, the monumental look, perfect for your Christmas lunch.

Alas (right) not all hair styles truly reflect the 21st century Christmas tradition but somebody always wants to stand out. Welcome everybody to your table!

We wish all our readers a very happy Christmas and all best wishes for the New Year.

‘How do I love Thee?’

‘Let me count the ways’

Terroir has been counting the ways to love and honour a landscape.

In September of this year we wrote about the process of influencing the quality of development proposed for one’s own ‘back yard’ (‘Qimby’ Blog 167). We had been participating in a local planning inquiry over a development proposal which many individuals and local organisations considered to be at best inappropriate and at worst disastrous.

Image right and below © Jan Sharman

The original planning application had been refused by the local planning authority (largely on heritage grounds) and the developer had appealed the decision. Regular readers will know that the original 4 days allocated to the resulting planning inquiry were woefully inadequate and a further five days were timetabled for the end of November.

We’ve now come though the ordeal. It was hard work and time consuming – and that was just for those of us watching from the side lines! Our barrister, town planner and ever faithful local councillors were in the thick of it. One thing was clear, however: it is extraordinary how many ways there are to represent the social and cultural value of a chunk of real estate, but it is extrordinarily difficult to assess the comparative value of all these perceived merits in terms of financial gain and loss.

Our title quote is, of course, from Elizabeth Barrett Browning, one of the ‘Romantic Poets’ of the later 18th/early 19th centuries, whose numbers included Wordsworth, Shelley, Keats and Coleridge. According to Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Romantic_poetry whose author can probably sum up the key ingredients of romantic poetry better than Terroir), the movement was “a strong reaction and protest against the bondage of rule and custom…”. Although obviously of its time, we can sympathise with this statement; it seems the difficulty of evaluating an ‘intangible asset’ is nothing new!

Image right: Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=230346

Before you shout that Barrett Browning’s sonnet No. 43 was a love poem to a human being not a landscape, let me remind you how Wordsworth turned the Lake District from wilderness to a romantic and desirable destination. We suggest (only slightly tongue in cheek) that there is a direct link between the 1804 poem, ‘I wandered lonely as a cloud’ (based on an earlier encounter with wild daffodils on the shores of Ullswater), and the designation of the Lake District as one of England’s first two National Parks (1951) and its later upgrading to a UNESCO World Heritage Site (2017).

Above: a selection of National Parks, from left to right, Peak District, South Downs, Lake District and Snowdonia

Today, the selection, protection and honouring of our special landscapes, buildings and other forms of cultural heritage is a complicated, complex and bureaucratic process. It ranges from international to very local levels. Each heritage ‘type’ has its own criteria for designation and its own specifics for assessing its significance in a planning appeal, such as the one we experienced.

Tell a barrister, appearing for the appellant, that a proposed development is inappropriate because of a few mountains, a lake and a bunch of daffodils (or whatever applies to your own particular back yard) and they will laugh in your face. Tell them that it lies in or near a landscape or cultural feature that is ‘designated’, and they will have to take some sort of notice.

But, without a campaigner of the calibre of Wordsworth, nor the timescale it took to turn the Lake District into a National Park, modern planning inquiries involve many legal wrangles about the niceties of planning policies and/or the significance attributed to a view from say a specific Conservation Area. Romance just doesn’t come into it, but hard graft does.

As an illustration of the complexity of the answer to ‘How do I love thee?’, we have listed below a very few of the policies, designations and guidance which were relevant to the assessment of, in our case, the development of tall buildings on a piece of local townscape. This list is by no means exhaustive.

National Planning Policy Framework

County Council Highways policies

Borough Council policies and plans including topic and site specific strategies such as planning, housing, heritage, flooding, biodiversity and a great deal more

Designations relevant to this particular site: a National Landscape, Historic England Listed Buildings, a Registered Park & Garden, locally Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas (5 relevant CAs in our case).

Of the illustrations below, only one applies to our case (Gatton Park, far right) but all are examples specific designations.

A basketful of other requirements and guidance were also relevant to our specific inquiry. Here is just a small selection to ilustrate the diversity:

Public Sector Equality Duty

Active Travel England Guidance

BRE Guidance - Daylight Sunlight & Overshadowing Assessment

Guidelines for Landscape and Visual Impact Assessment

Daffodils - sadly no, although Gatton Park is locally famous for its snowdrops

Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s list is much less prescriptive and much more romantic. It’s just a pity she didn’t dedicate the poem to brown field site adjacent to our local railway station.

I love thee to the depth and breadth and height

My soul can reach, when feeling out of sight

For the ends of being and ideal grace.

I love thee to the level of every day's

Most quiet need, by sun and candle-light.

I love thee freely, as men strive for right.

I love thee purely, as they turn from praise.

I love thee with the passion put to use

In my old griefs, and with my childhood's faith.

I love thee with a love I seemed to lose

With my lost saints. I love thee with the breath,

Smiles, tears, of all my life; and, if God choose,

I shall but love thee better after death.

Confused of Kingston

How many towns in the world are called Kingston? Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_places_called_Kingston) suggests that there are quite a lot, even if you ignore the settlements which are defined as hamlets, villages or suburbs. The impact of a largely male British monarchy and the enormity of the British Empire ensure that Kingston is a fairly common name throughout the English speaking world. ‘English’ in the geographical or political sense may also be significant: Wiki’s list for Scotland only records the name against a hamlet, a village and a district of Glasgow and the website has no listing at all for Wales. The fact that the letter ‘K’ does not exist in the Welsh alphabet may also be a factor.

This year, Terroir visited both Kingston upon Hull (for a Coldplay gig - yes, really) and Kingston-upon-Thames; or maybe it was Kingston upon Thames or Kingston-on-Thames. All these monikers have been assigned to this confusing town and we believe it is currently using the name Kingston upon Thames, a compromise between grandeur and hyphenation.

The reason for the trip to Kingston-up-river-from-London was to complete a further section of the London Loop which was obviously invented in Kingston, as its full name is the London Outer Orbital Path (no hyphenation). “The London Outer Orbital Path, or LOOP, almost completely encircles Greater London. Nearly 150 miles are split into 24 sections between Erith station [east London, south of the Thames} and Purfleet [east London, north of the river].’ (https://tfl.gov.uk/modes/walking/loop-walk). Of course the Loop (Sorry LOOP) crosses the Thames to the west of London at, wait for it, Kingston upon Thames.

King Egbert: By Unknown author - http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/FullDisplay.aspx?ref=Royal_MS_14_B_V, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=28008709

Bob Marley: By Avda - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24942405

Kingston upon Thames means different things to different people. To part of the Terroir South team it means standing on Kingston Bridge waiting for Bradley Wiggins to race past (literally) during the 2012 Olympics. To many of our friends, ‘going to Kingston’ means failure in local shopping venues so heading to the Kingston shops (including a famous department store) to find that perfect outfit. Meanwhile, thousands of students sign up at Kingston University while John Everett Millais based his picture of Ophelia on (or rather in) Kingston’s other water way, the Hogsmill.

This all seems pretty clear cut, but controversy and confusion have a long history in the town. In 838, King Egbert (pictured above) was in charge of what was then a border town between Wessex (who knew that Wessex spread so far east?) and the mighty, midland territory of Mercia.

By the tenth century Mercia’s King Athelstan had combined the two and had, apparently, created England (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kingston_upon_Thames). As a result, “According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, two tenth-century kings were consecrated in Kingston: Æthelstan (925), and Æthelred the Unready (978).” Clear enough, but further coronation evidence is “less substantial”. Perhaps things would have been easier if there has been more diversity in royal initials (no wonder explanatory suffixes were so necessary). Apparently the uncertainty relates to Edward the Elder (902), Edmund I (939), Eadred (946), Eadwig (956), Edgar the Peaceful (c. 960) and Edward the Martyr (975).”

Today, Kingston’s ‘Coronation stone’ provides an impressive (if somewhat surprisingly brightly coloured) focal point between the town’s Guildhall and the Hogsmill River. It may not be an actual coronation stone and may not be as old as the Saxon kings, but it does what Kingston has been doing for centuries – combining old and new in a constant evolution of form and function.

Bringing confusion right up to date means that Kingston’s best known bureaucratic oddity has finally been obliterated. For years, Kingston upon Thames was famous for being the County Town located outside it’s county boundaries. According to Wkipedia, Kingston has been a royal manor, a parish, a borough (since 1441) and became a formal Municipal Borough in 1836. Known for many years as a Royal Borough, King George finally formalised even that title in 1927.

Kingston’s role as a County Town started in 1893 when Surrey County Council moved HQ from Newington to a new and very grand County Hall in Penrhyn Road, Kingston. In 1965, the town became part of the London Borough of Kingston upon Thames (no hyphens) but, despite being located in London, the Penrhyn Road premises remained the focus of all things Surrey. Not surprising then that, for the next 35 years, Surrey’s County Hall’s location became a quiz question until the Council finally decided to vacate the imposing, Victorian, Grade II listed building for slightly less grandiose premises in Reigate - yes, in Surrey- but almost as far as you can get from Kingston, without being, once again, out of County. Welcome to the Far East.

As a post script, Surrey County Council itself will become history in April 2027, with the creation of two unitary Councils called, imaginatively, East Surrey and West Surrey.

Currently, the Kingston County Hall is under scaffolding for convertion into “high quality, residential led, mixed used[sic] development”. If you want to live in the land of the Saxon Kings, which your friends will mistake for Yorkshire or Jamaica, then you can register your interest in advance. Confusion is included at no extra cost.

Hopetown or Hadestown?

They sound diametrically opposed but in so many ways they are scarily similar. Could you lead your lover out of Hopetown without looking back? I don’t think so.

But let’s be clear: Hopetown is the optimistically named railway-works-now-museum in Darlington, County Durham, while Hadestown is the name of a Broadway musical with lyrics like

“On the road to hell there was a railroad track”

Or

“Lover you were gone so long

Lover, I was lonesome

So I built a foundry

In the ground beneath your feet

Here, I fashioned things of steel

Oil drums and automobiles

Then I kept that furnace fed

With the fossils of the dead”

I suppose we always suspected that Hades was both King of the underworld and patron saint of all things powered by coal aka “the fossils of the dead” (although I think coal is strictly vegetarian so the analogy may well be flawed!).

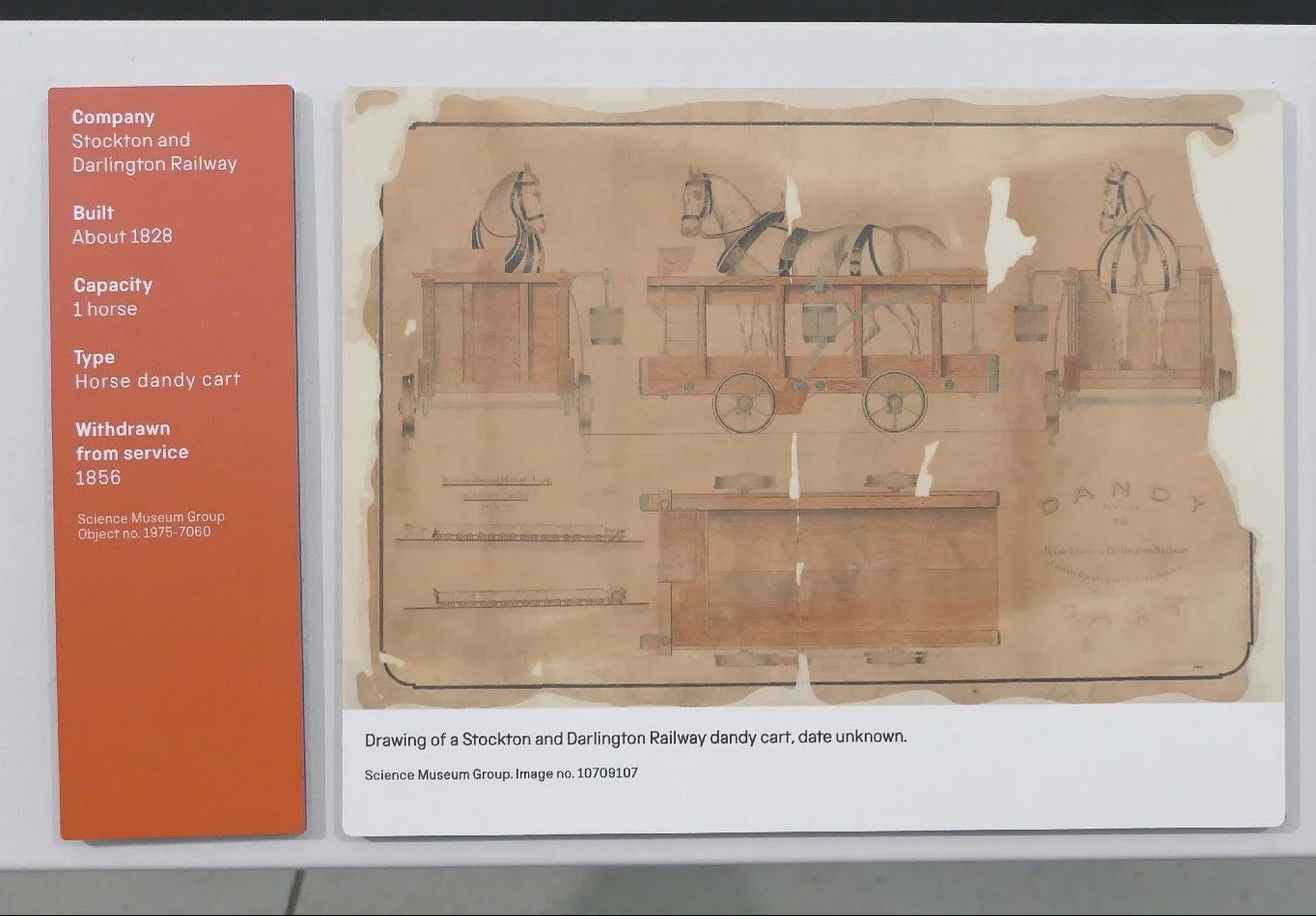

As part of our homage to Rail200 (Part 1 is in the previous blog) we visited the Hopetown Railway Museum in Darlington. Somewhere we had read that ‘Hopetown’ was so called because a carriage works, which the Stockton and Darlington Railway propsed to build in this area, gave some hope for a better or perhaps more secure future for the local workforce. A brief Internet research makes no mention of this theory but it seems entirely credible and an obvious candidate for another musical.

The carriage works opened in 1853, its brief to build and maintain ‘two axle railway carriages’ for passemgers on the Stockton and Darlington Railway (SDR).

The site, a little under a mile to the north of the centre of Darlington, was already the location of the town’s first railway station (right). If you wonder why it was so far away from the town centre we must remind you that the primary function of the SDR at that time was the delivery of coal from local collieries to the river ports of Stockton on Tees!

With the subsequent construction of other railways on other routes, a more central town station was constructed in 1841 (others would follow) and the original SDR station renamed North Road. As its later name suggests, this location was also handy for the Great North Road heading to Newcastle.

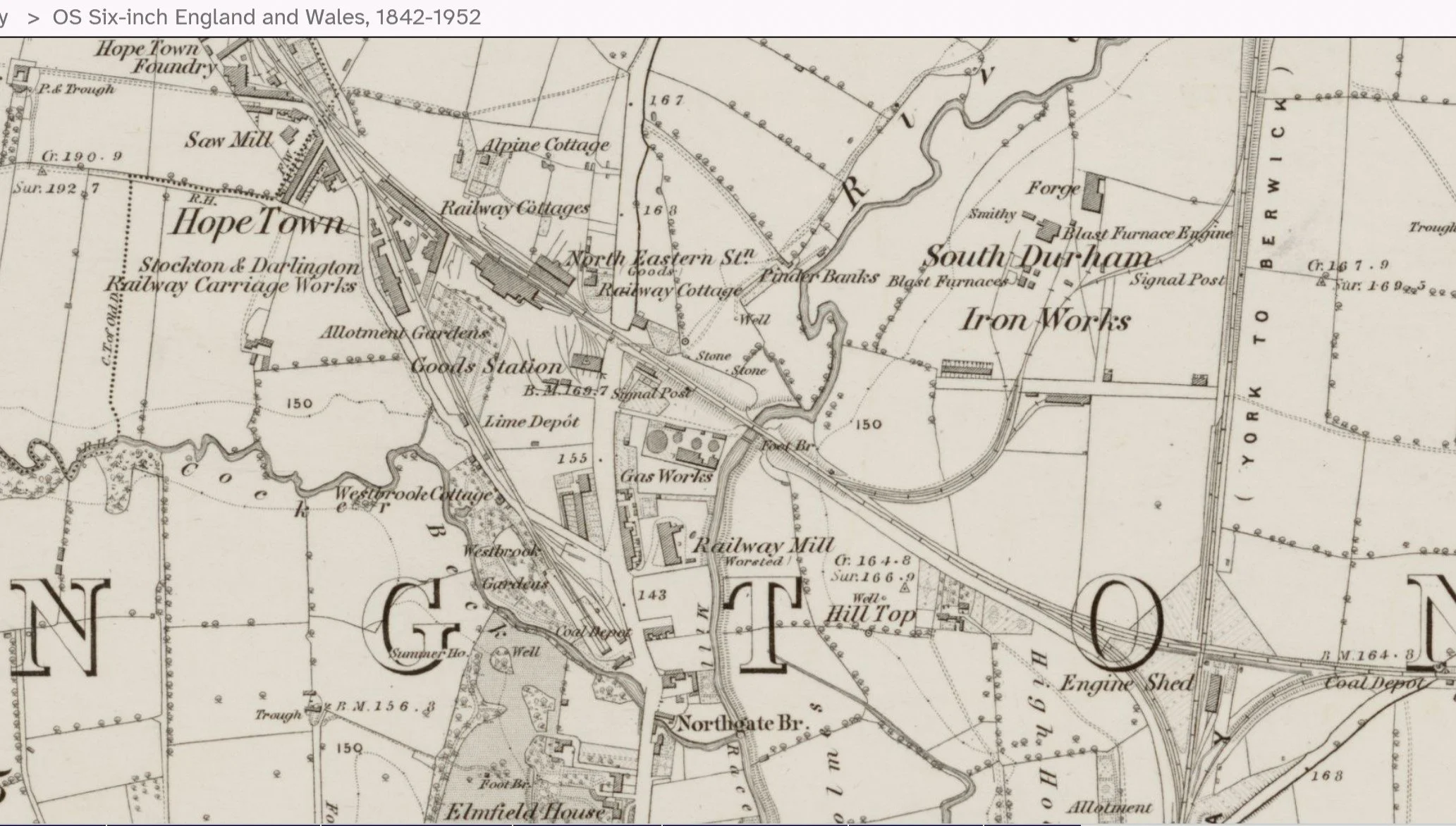

Maps published around the time of the carriage works’ construction indicate that the Hopetown area was still largely rural but the impact of ‘King Coal’ is already very evident. Apart from the railway infrastructure (the Hopetown foundry, goods’ sidings and railway workers cottages) there is already a gas works and the South Durham Iron Works.

Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland' https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

Ironically, the carriage works closed in the 1880’s but the Hopetown name stuck. Perhaps some of the original ‘Hopefuls’ moved to the ‘Darlington Works’ (more concerned with locomotives than rolling stock) which were established in 1863 or to the ‘North Road Shops’ on the opposite side of the railroad tracks at the Hopetown site.

Although threatened with closure many times, North Road (Darlington) Station still survives (Bishop Auckland to Darlington in around 26 minutes) but the original station building and the Hopetown Carriage Works area were acquired by Darlington Borough Council in the 1980s and became part of the Darlington Railway Centre and Museum. When Terroir visited in September Hopetown was heaving, with a very varied selection of activities and displays.

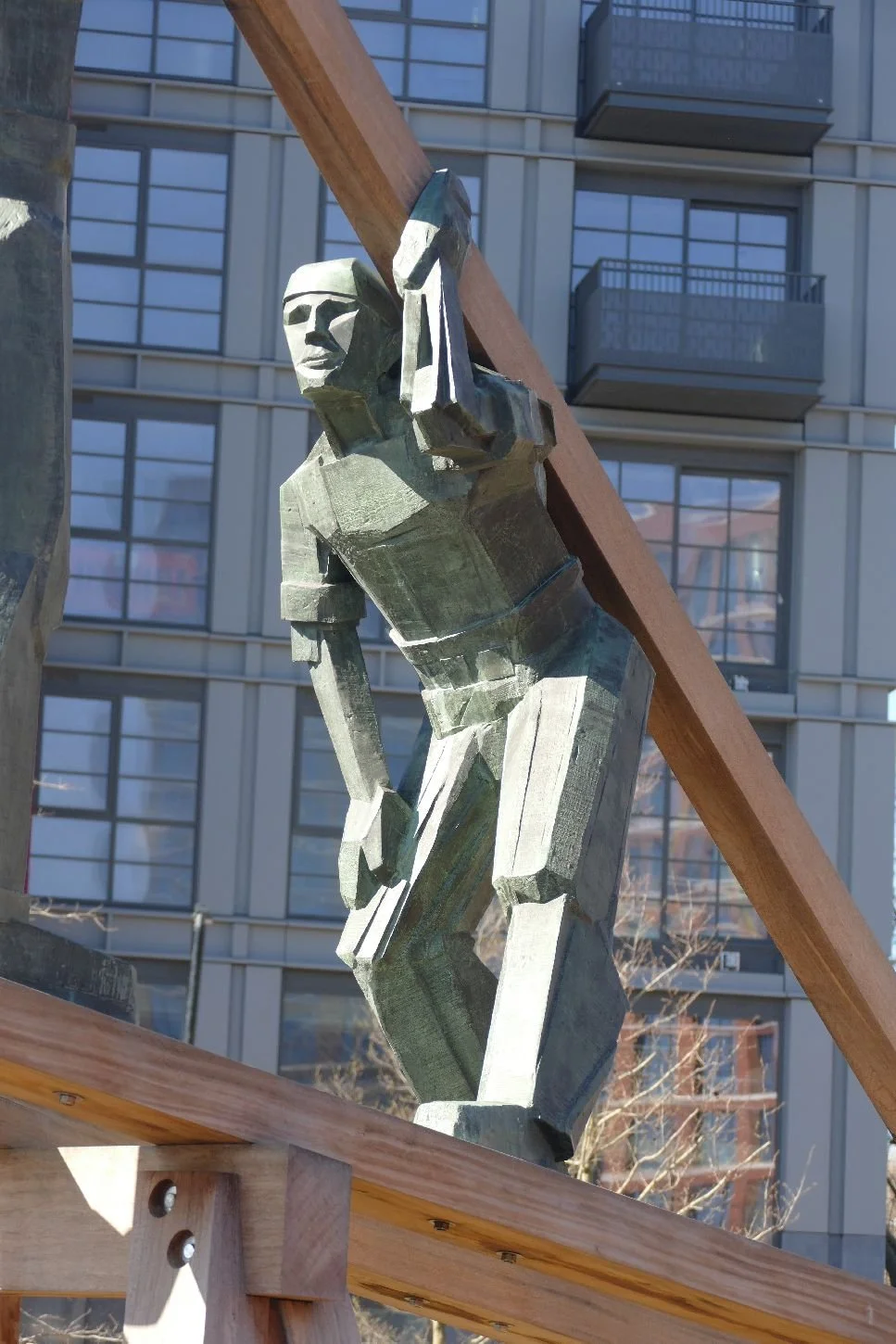

We were particularly delighted with a statue – not of Hades - but of Prudentia who, according to the Northern Echo (https://www.thenorthernecho.co.uk/news/25185272.prudentia-back-darlington/)

once adorned the offices of the Prudential Insurance Company in Darlington. After an eventful career, including many years in a packing case, she has finally been released to adorn a garden adjacent to the preserved North Road Station building. She is obviously recommending the use of a mirror (cunningly disguised as a table tennis bat) to escape from Hades and the Greek underworld.

But the reference to Hadestown in this blog was not just a jokey play on words conjured up by the discovery of a place called Hopetown (although that was, indeed, the start of it). We knew of course, that County Durham was a colliery county. We knew that the Stockton and Darlington Railway was founded on coal and fuelled by the same stuff. We know that mining was not a career path which we would have wished to follow, out of economic necessity or for any other reason. Paintings at the Miners’ Gallery in Bishop Auckland, really drove home the reality of Hades’ underworld for a huge section of the local population.

Above: Images from the Bishop Auckland Mining Art Gallery Guide Book

Our last story from the land of Hope and Hades is, therefore, about the intimate link between geology, technology and design. This interaction was beautifully illustrated by the historic wagon displays inside the mighty exhibition shed at Shildon. The Hopetown carriage works had been relatively short lived; transporting people didn’t go out of fashion but the technology changed and production moved to York. The Shildon works fared better. By converting from locomotive construction and repair to the production of wagons, Shildon continued in production for over 150 years, creating wagons adapted to transport various raw materials, manufactured goods and a variety of other types of freight. Here follows a selection of our favourite design adaptations to accomodate changing cargoes, new materials and methods of loading and unloading.

The basic coal wagon or chaldron wagon (above left) was the staple on horse drawn railways but as demand for coal expanded, so did the design of the wagons to allow easy bulk delivery. No doors became side doors or doors in the base of the wagon. Construction changed to keep up with modern materials which were longer lasting or could be easily maintained.

Horses hauled wagons for centuries but ended up being transported by them instead (below).

Carrying liquids was a new challenge and required a complete rethink of materials and shape (below).

Well wagons were designed to carry heavy vehicles or large loads by creating additional depth between the wagon wheels (below).

And here is our all time favourite for going just that extra mile - the sewage disosal wagon.

We suggest that neither the mythical Hadestown nor the actual Hopetown developed the ingenuity or adaptabilty to cope with changing circumstances. Condemned to be myth or museum respectively, they could be a salutary comment on the future of rail transport. So much of railway engineering is already classed as heritage. Is sufficient realistically being developed to meet the challenges of climate change and competition from other transport modes? Well, at least we have the Musical to look forward to.

Grumpy Gricer

Glenfinnan Railway Viaduct © Ken Morris

Many of Britain’s classic landscapes are influenced – in a good way - by what we now call ‘transport infrastructure’. The Glenfinnan Railway Viaduct, striding across its Highland glen with breathtaking, late Victorian assurance, was admired and photographed long before J K Rowling and film industry location scouts made it world famous.

But we can also say that much of British transportation is enhanced by beautiful landscapes. The M6 south of Tebay passes though Cumbria via the magnificent Lune Gorge. For the passenger at least, the view of fells, plumped up like enormous green velvet cushions threaded by tumbling gills, is magnificent. But for the walker, or driver on the A685, the valley will never look or sound the same again.

By Don Burgess, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=13145536

What has brought on this stumbling discourse on the relationship between transport and landscape?

The answer is ‘Railway 200’, described as “… the 200th anniversary of the birth of the modern railway. Britain and the world changed forever. Railway 200 celebrates the past, present and future of rail.” (https://railway200.co.uk/about-railway-200/).

The website continues with a lot of public relations style prose stressing how wonderful the railways were and are and will be.

Terroir spent a few days in County Durham, visiting the land of the Stockton and Darlington Railway. It was fascinating, fun, nostalgic, frustrating, informative, misleading, advertorial and well worth the visit. There was even a rail replacement stage coach (image right - can you spot it?). But the experience also raised a lot of questions and unexpected answers, if you were willing to look beneath the hype.

For Terroir, the core message was ‘Myth and Money’.

The Big Myth – the Stockton and Darlington Railway was the first railway.

The Railway 200 website says: “The Stockton & Darlington Railway opened on September 27, 1825, connecting places, people, communities and ideas and ultimately transforming the world.”

But surely, there have been transport routes which employed wheeled vehicles guided by two parallel rails (ie a ‘railway’) in use in many countries long before the September 1825? The Greeks were certainly onto something when they used ‘rutways’ to guide flatbed trucks to carry ships and cargo across the Corinth Isthmus around 600 BCE. The wheel was guided in a rut, instead of on a rail, but the basic principle is enough for some to call it the first railway.

Fast forward a few thousand years to find that ‘inclined railways’ (with rails not ruts) existed in mines from the early 17th century, using horses and/or gravity to provide the motive power. Above ground horse drawn ‘tramways’ were used in England frm the early 18th century, usually to shift materials from source (eg quarries) to boats.

‘The Railway 200’ people are careful to note that 27th September is the birthday of the ‘modern railway’. If ‘modern’ means the first use of steam engines, then we find that steam locomotives were hauling trains before 1825.

According to (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Steam_locomotive) it was Richard Trevithick who should be credited with creating the earliest steam locomotive. This summer’s celebrations did make a passing reference to Trevithick but it was George Stephenson (right) who took all the engineering honours.

Image right: Bronze statue of Robert Stephenson by Carlo Marochetti, originally erected at Euston station in 1871

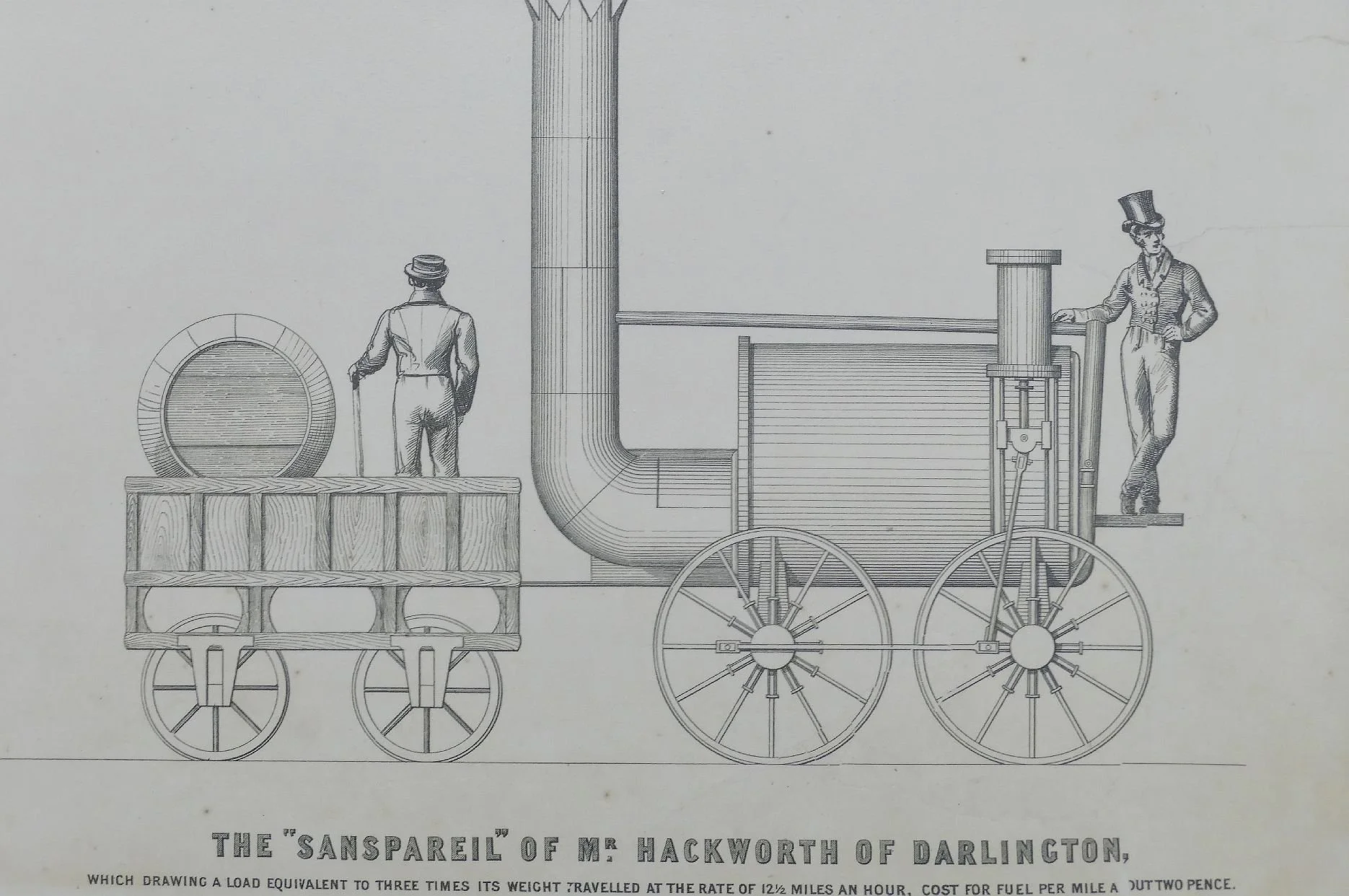

Another side-lined engineer was Timothy Hackworth, five years younger than Stephenson but born in the same Northumbrian colliery village. TH built a number of steam locomotives, his earliest being the Sans Pareil. Granted it blew up at one point but then so did Stephenson’s Locomotion No 1.

Hands up all those Terroir readers who have actually heard of the adventures of Master Hackworth (1786 – 1850)? Be quiet Terroir North. We know that you know!

So forget first steam engines as defining a modern railway. Is the modern railway about hauling coal trucks from collieries or carrying paying passengers? Nope - Trevithick also managed both those before 1825.

So what was so special about September 27th 1825? It was actually the birthday of the Stockton and Darlington Railway company, not of steam hauled trains, not of passenger on trains, but the day the first railway company went into commercial operation. That day was celebrated in style with crowds of onlookers. The SDR put on a special train with wagons carrying coal and wagons carrying people and a wagon carrying a brass band. It was hauled by ‘Locomotion’ and travelled 18 miles from Shildon to Stockton. It seems to have been a splendid and exciting pageant; possibly the first modern use of a good promotional team, as well?

Locomotion hauling coal, passengers and a brass band across the Skerne Bridge

So, Terroir wonders, was the 27th September 1825 celebrating railways as such, or just a new transport business model? Was the engineering prowess, the industrial revolution’s hunger for coal, the need for an Act of Parliament andextensive use of Compulsory Purchase Orders just part of the back story? We are sure the answer is no. That epic journey must have been a celebration of engineering prowess, as well as a recognition of the business opportunities offered by coal, the industrial revolution and the empire. Who can blame the shareholders for making it into a ‘right good do’.

A one hundreth anniversary celebration of railways was also held in England in 1925. Perhaps we shouldn’t blame the big four railway companies for using the Stockton and Darlington as an excuse for a celebration. The London and North Eastern Railway must have been particularly keen on the location although a date in July was deemed more appropriate than September. It must have seemed the perfect opportunity for a post war knees up, and celebration for the whole of Britain and its Empire.

It all happened again in August 1975, although ironically, this event was more of a celebratory farewell to steam than the welcome shindig of 150 years ago.

So it’s no surprise that August and September 2025 was in the diary for another railway extravaganza. The Rail 200 website again: “During 2025 Network Rail, alongside many other rail industry partners, will be celebrating rail’s remarkable past, recognise its importance today, and look forward to its future.” (https://www.networkrail.co.uk/who-we-are/our-history/railway-200/).

So why did Terroir return home with a few grumpy nit-picks lurking in the back of the mind? Your honour, I submit the following evidence. The first observation is ridiculously simple: the number of those who were asking ‘why this date’ or saying ‘it’s the wrong date’. How come so many people thought of it as a 200th anniversary of railways in general? We got the message that “Railway 200 will showcase how the railway shaped and continues to shape national life” but not that it was the third in a series of railway celebrations based on the opening of the Stockton and Darlington Railway. Where was any information which illustrated the 1925 and ’75 celebrations? But does it really matter? Yes, to some people it did.

The second nit-pick is much more serious. Where was the replica engine of Locomotion No.1? It was billed to appear on the day we were visiting. No sign of it, not even an announcement that the scheduled service had been cancelled.

The third nit-pick was distinctly worrying. The razzamatazz and display of shiny locomotives prepared us for exhibits which would talk up the UK railway industry, something which the majority of visitors probably ignored.

On wandering into a display on the future of railways, however (apparently presented by the Rail 200 partners), my propaganda klaxon started bleating. Now no-one in Terroir has a PhD in mechanical engineering or computer science but we are interested in sustainability, climate change and new technology. We can also read and, occasionally, we are quite good at reading between the lines or spotting very selective use of information and data. The display was very selective indeed.

Appalled, I expressed my indignation out loud. A young engineer standing nearby looked over and substantiated my views. As we left, the trio on duty at the entrance to the display were – politely - informed of my/our opinions! They took it well but I doubt the feedback went much further.

Next time we will be looking at the fun stuff – yes really - and how important geology is in the design of wagons.

And if you are out there, Mr Young Engineer, it was great to meet you and I do hope you raised those dodgy information boards with your colleagues.

Has Lyon Gone to the Dogs?

Terroir says absolutely not. But there are a lot more animals in residence than there used to be.

Faithful readers may remember that we visited the city in the spring of 2022. It was our first overseas outing since the pandemic and despite anxieties over Covid passports (which no one wanted to look at) and European exit requirements (time expired some 10 hours after our departure) we had a splendid weekend à la Lyonnaise.

Last month, we returned to the capital of French gastronomy for just 24 hours, en route between Nice and Lille. We stressed over how we should spend our brief visit but, in the end, our choices delivered an unexpected mélange of plants, animals and architecture.

Back in 2022, our experience of Lyon Part-Dieu railway station was somewhat marred by extensive city redevelopment works. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose!

The large chalky white cliff to our left in the above 2025 image is the in-your-face wall of the Lyon Westfield (makes East London’s Stratford version look positively inviting). When we climbed those steps in the spring of 2022 we discovered that the shopping centre had opened, and attempts were being made to create some sort of sitting out area. To be honest, and despite the columnar tower block, it reminded us of a café in a chilly and deserted mountain top ski resort.

Turning around, we discovered – no, not a dark, wintry pond broken out of the surrounding ice – but a planting bed set in a hell of hard paving. If nothing else, this area at least hinted at ‘potential’.

Here it is in the autumn of 2025.

It’s taken us a while to understand why we were somewhat underwhelmed.

Set in its hard, rocky, stony upland and surrounded by urban cliffs, it should be an elevated oasis, a place to rest in an otherwise unrelieved, grey, commercial landscape. But at first sight, there wasn’t a soul there. Only on the periphery, in a rare sheltered and enclosed nook, with trees to guard your back and shrubs to cast some shade, did we come across homo sapiens.

Subtly but effectively fenced off, there was no access, not even a fenced pathway from which to view the oasis interior. Texture, pattern, colour? Yes, and lovely if you can get close up, but it is a drop in the ocean In this substantial area of paved desert.

Room for one more moan? It seemed ‘over-signed’ (see images below). One of us felt like a school child with a condescending teacher, telling us what to look for. Please give us an information board or two at entry points, but let those who do stop to enjoy the ‘garden’ (or ‘green-washing’?) wander round without constant interruption from a cutesy interpretation board which distracts us from the flowers, butterflies, birds and herbs we’re supposed to be enjoying. I think we did see a couple of white butterflies but it was so easy to ‘read and walk on’ and miss the actual habitat altogether.

We were disappointed of course - such wasted opportunities are so typical of ‘tick box’ design, of provision of the bare minimum and, probably, ‘green-washing’ - but it could have been worse. Maybe!

At the other end of town, there is a museum which we had yet to visit. In 2022, we wrote, “The southern tip of the presqu’ile lies at the confluence of the two rivers. It’s somewhere you feel you should go, but if your tourist programme doesn’t feature the Aquarium and the two museums located in this area, we get the feeling that it’s slightly off the beaten track.” We were right, in as much as The Musée des Confluences, located on the Presqu'île, is a very long walk from Lyon Centre Ville or Vieux Lyon. Thankfully there is a beaten track all the way there and it’s called the T1 Tram line.

The confluence of the mighty River Rhône with the only slightly more modest River Saône (flowing down from the nearly-in-Switzerland Vosges Mountains to the north east) is a spectacular piece of waterscape and the Museum is located right at the heart of the river junction.

The scale and vibrancy of some of the local architecture matches the physical geography of the site, but sadly the walk from the tramstop to the Museum is a real challenge in terms of townscape (nul point), acessibility and transport planning. Here’s a couple of the good bits.

For those familiar with London Museums, the Musée des Confluences is, in terms of content, a combination of the Natural History Museum and the ethnography side of the Horniman Museum, altbeit without their respective gardens. Due to the length of time and energy required to reach the confluence we took the museum content at some speed but did enjoy, and feel stimulated by, what we saw.

This extract from the museum website sums up the complex content very neatly: “Journeys through time and on all 5 continents, the exhibitions tell the story of humankind and their place in a living world and address such great universal subjects as the origins of the earth and life itself.” https://museedesconfluences.fr/en/welcome-museum Big stuff!

We saw displays on what felt like every aspect of human society: rituals and rites of passage, economy, religion, costume, art, music and, we’re pleased to say, attitudes to land and landscape. A tiny, tiny taster is included here, including some of those animals which we mentioned at the start, and which now seem to inhabit this part of Lyon.

A huge variety of prehistoric, endangered and thriving wildlife is displayed (above) and is popuar with the younger visitor. Canines were not exhibited in disproportionate numbers, so I think it is safe to say that Lyon has not gone to the dogs, although deer may be an issue very soon.

Art in many different media (including a vibrant display of costumes) was probably attractive to all ages, although may be disappointing to dog lovers.

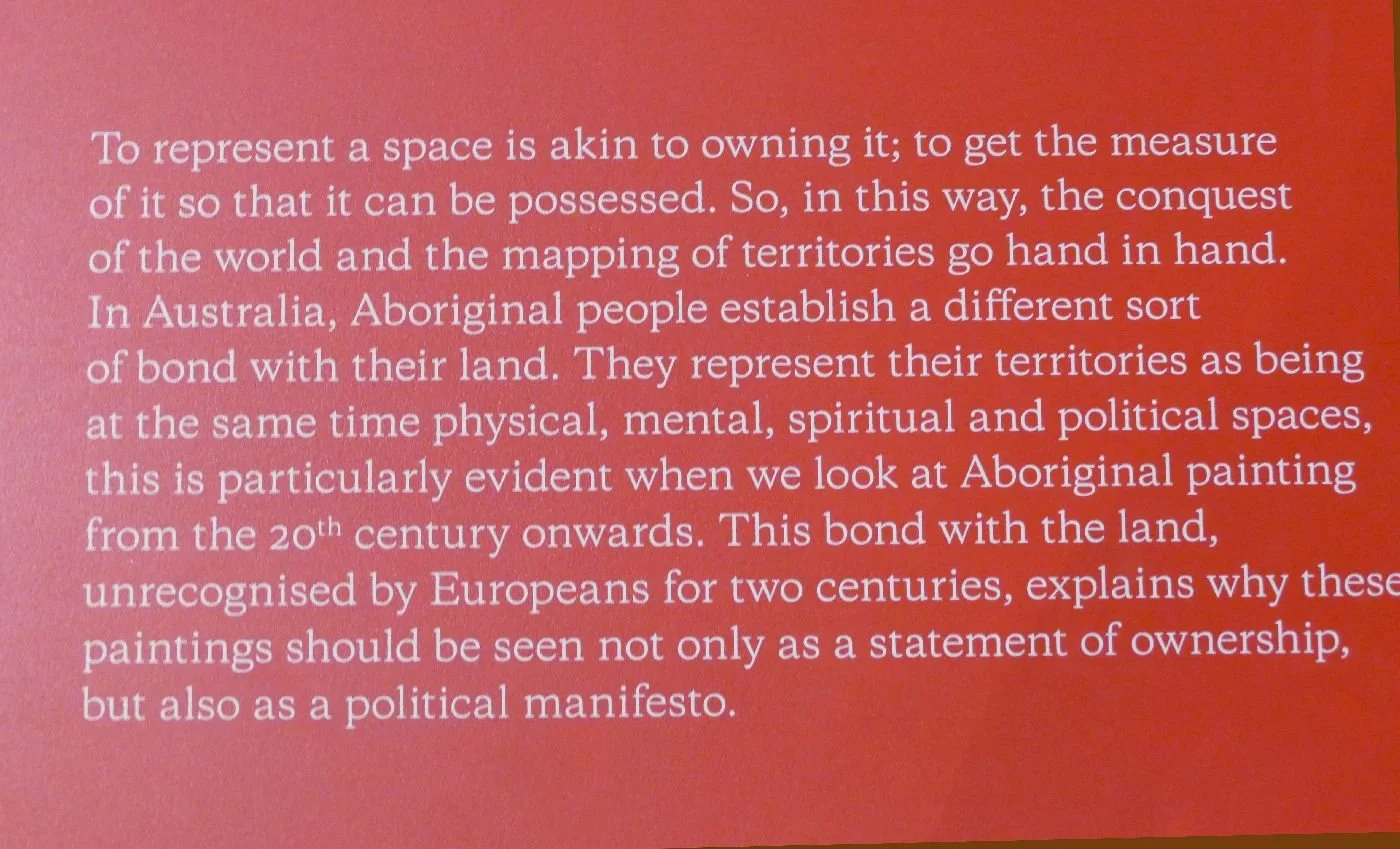

But we will leave you with a display which particularly resonated with Terroir. The sign below was located adjacent to the Australian aborginal art shown above right. So here’s to Lyon and landscape.

Is Nice still nice?

We thought picture postcards had long been a thing of the past. Do you remember the dreaded trawling of souvenir shops to buy suitable cardboard views of wherever you had gone on holiday? Do you remember the subsequent trips to find a post office and the troublesome business of purchasing sufficient stamps, of suitable value, to get the pesky little pictures back to Blighty before you did? And perhaps worst of all, sitting down and writing them (even if you did use the same message on each one), finding the appropriate address, sticking on the stamps and searching for a letter box, when you could have been sightseeing, sunbathing, strolling down the promenade, climbing a mountain, sampling the local beer or cuisine, or just reading a book in the sunshine? And, of course, the final horror of returning home, having forgotten to post them in the country of origin.

Well, apparently postcards are back. Apparently your children’s children (already more skilled in navigating the digital world than you ever were) now expect their grandparents to go through the whole card, stamp and letter box routine, all over again.

Terroir, of course, believes in computer compromises and we have sent you blog-cards before (from Italy and Sicily). Though we know that you are digitally savvy grownups, we are now risking another set of electronic postcards. You are welcome to show them to any grandchildren you might know, if you think they might be remotely interested.

Greetings from the French Riviera

Is Nice a cliché? Well, Terroir wasn’t able to interview any Goths, Ligurians, Greeks, Gauls, Romans, Byzantynes, Lombards, Francs, Saracens, Normans, the Counts of Provence, the Grimaldis of Monaco, the Counts of Savoy, Turks, French, Hapsburgs, Sardinians, Sicilians or la famille Bonaparte, who all seem to have been involved in the city right up to the 19th century. In 1860, the Duke of Savoie, Victor-Emmanuel II, conceded Nice and Savoie to the French, represented by Emperor Napoleon III (Bonaparte’s nephew; think patron of Haussman in Paris). All this roughly – very roughly – in that order.

Squeezed between the Alps and the Mediterranean, Nice seems to have always been a nice place to relax if you were on the side of whoever was in charge. Napoleon III was keen on railways so, one suspects, tourism started to became a thing - until Queen Victoria and the British medical profession spotted its potential for relaxation and therapy and Nice became, not just a thing, but just huge.

Nice’s most famous road, the “Camin deis Anglés” (in the Niꞔois dialect) was constructed with British money to provide work for the starving poor following a severe winter in 1820 (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Promenade_des_Anglais). When the French took over in 1860 (and franꞔais became the required language) the Camin was reworked to become the Promenade des Anglais.

So what is Terroir’s take on modern Nice?

Townscape: we liked the quirky urban art - or is it seating for the older or more inebriated visitor?

Modern design: these sleek trams really do complement the city’s architecture as well as enable a huge network of car-free streets.

Beach accessibility: you can pay (below left), or you can find that short stretch of ‘Plage pour tous’ (centre) - a good option for a September dip but probably rammed in summer. Definitely limited if your wheel chair or walking sticks aren’t good on shingle. Nobody stands in the way of the maintenance vehicle, however (right)!

And they never mention the flight path for nearby Nice Airport. So handy for the - pardon, I didn’t quite hear that? - Riviera.

Climate change? The relatively recently re-designed Place Massena is to be redesigned again, to reduce its expansive hard surfaces and increase planting and other forms of climate change resilience. Other city modifications include the punctuation of the Promenade des Anglais with less than lovely shaded sitting areas (although we suspect these were temporary structures to cater for the recent Ironman France event) and some very short and highly maintained, species poor, ridiculousy bright green grass between a section of tram lines). Please don’t tell us it was Astroturf!

Now haute couture should be a hot, and very photographic, topic. It seemed, however, that September fashions are fairly low key this year. Below are a couple of our favourites and a reminder that the French scooter is an all-singing, all-dancing workhorse which enables riders to deliver parcels and take children to school without a whimper.

Of course, we also visited the occasional garden and thoroughy enjoyed a gentle stroll through the park surrounding the Villa Messina Musée d’Art et d’Histoire. It was well planted and well maintained but a delightful art installation gave us the best horticultural fashion advice of the trip. You can just glimpse the yellow framework on the left handside of the entrance (left), with detailed designs below.

We leave you with a couple of political comments, one from the beach and one from an up market hotel garden.

Dear Gran and Grandad - hop you are well. Love from Terroir.

QIMBY

We’ve had a very busy time recently, trying out a new acronym. Thankfully, someone has reinvented the Nimby and members of Terroir South have recently been part of a team fighting for ‘Quality in My Back Yard’.

As Europeans we are very fortunate to live in countries which practice democracy in one form or another. We can ‘have our say’ or, in other words, attempt to influence who governs us or who gets planning permission to build in our back yards.

Sitting through a planning inquiry as a local resident gives you plenty of time to think about how we manage our democracy. Is it fair? Is it accessible? Is it easy to understand? Not really. Is it possible to make your voice heard? Yes, if you have time and are good at organising your community. How we vote at national and local elections depends a lot on how our local community canvasses for its favourite representatives. It also depends on how we perceive tactical voting or whether we attend the local hustings.

In simplistic terms, what gets built in our back yards is mostly down to our local democracy. Of course we can say what we think about planning applications - if we understand how the system works. We can read about the proposal on the local authority website, submit written comments and, if it’s a big one, there will probably be consultation meetings open to the public or targeted at specific local community organisations. The final decision is taken by a planning committee made up of elected local councillors. Wishing you had voted differently at election time? It’s too late now.

If planning permission is refused, the applicant can register an appeal against the decision. Is it possible to participate in the process? Yes, if you have money. Is it adversarial? Yes, very. So it’s like a trial at the Old Bailey? Pretty much, as it involves legal representatives battling it out in front of a ‘judge’. The main difference is that, if that inappropriate development finally gets the go ahead, despite your best efforts, you’re stuck with it. You can’t apply for parole and have it pulled down on the basis of good behaviour. You can vote out a government or a local council, but your building will stay until someone realises it is full of asbestos, or crumbling concrete, or decides to redevelop the site.

On the other hand, a local community group can get involved in the process to influence the local landscape. It involves a huge amount of time and effort and, yes, that undemocratic commodity – money (thank goodness for crowd funding). Under the present system, if you really want to make an impact, you hire a barrister and a team of specialists to fight on your behalf.

© RRAG

One of us has seen a few planning inquiries from the inside but, as an ‘expert witness’, you give your evidence, you get cross examined and you leave. No one is going to pay you to sit in the back to watch it play out. So for one of us, watching the whole thing from beginning to end was a new experience – exciting, frustrating, nerve racking, infuriating and, at times, very boring!

Like any other court of law it is very formulaic in process but, thankfully, somewhat less anachronistic than the much older institution of criminal law. The ’judge’ is called an ‘inspector’ but you are still required to call her or him Ma’am or Sir. As an aside, we’ve heard this title pronounced Ma’am (long ‘a’), M’am (rhyming with ‘jam’) and Madam over the last few days. It doesn’t matter but it is bizarre. Barristers don’t wear wigs (but that doesn’t make the cross examination any less scary) and gowns are replaced by standard business attire.

With three teams of barristers and their entourages, the time allocated for our recent inquiry was insufficient and we reconvene in November. So it looks like no outcome until early 2026. Time and money is essential in this game.

And sorry about the lack of pictures.

The White and the Blue

All villages have a story to tell, but every account will vary according to the tale teller. Each narrator will have a different perspective. During our recent visit to the Danube Delta (see previous blog 165), we revelled in Romania’s wetland world, but we were also fascinated by the terrestrial environment of the village in which we stayed - Mila 23. So please, bear with Terroir, while we attempt a brief and very personal account of one of the Danube Delta’s inhabited islands.

As we mentioned in our ‘Greek and Romanian Geography’ blog, Mila 23 was the name of a village located 23 nautical miles from the Black Sea port of Sulina, on the old shipping route from the sea to the river port of Tulcea.

According to this aptly named website (https://www.discoverdanubedelta.com/mila23-village-in-the-middle-of-the-danube-delta/), 23 nautical miles was the distance which could be rowed in a day, thus making this location an obvious overnighting spot on this particular route through the delta.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the delta had been inhabited since around 4,000 BCE by agricultural, pastoral and fishing populations. The Mila 23 area seems to have reached the start of the 20th century as a lose collection of hamlets, but the following decades saw considerable change. The construction of the Sulina canal (carrying rather more mechanised forms of shipping by this time) bypassed Mila 23. Some delta drainage disrupted the pattern of fishing communities, and massive flooding in the 1970s resulted in some re-engineering of the main village.

As a result, a number of hamlets and habitations were deserted and the population became more concentrated within the central village but, with no shipping to service, Mila 23 had to seek a new economic base. One hopes that tourism, based largely on bird watching and fishing, is keeping the community alive.

Left: housing old and new

The old Sulina waterway is still an obvious and dominant characteristic of this village, but there is another, more colourful component, which is equally important: the love of blue and white. These are the colours of this Lipovan community, a Russian-origin people, who have clearly retained their traditions, including the Russian (rather than Romanian) Orthodox Church.

The more we explored the Mila 23 island, the more we found traditional and modern intertwined. We mentioned, in the last blog, the importance of the Delta reed harvest and the versatility of this crop. Thatching is an obvious use but thatch and tiles now combine in many combinations and also illustrate the variety of options for the use of the traditional blue and white colour scheme (see below).

Exhibits in one of the local museums illustrate the blending of Russian flavours with a Romanian wetland environment. It looks like the reeds (below left) are available as fuel and have clearly been used as building material (below centre). And are those samovars and Russian Orthodox religious icons (below right)?

Moving outside, we swap bread paddles for boat paddles. Boats, fishing tackle and decorative wetland imagery must be as symptomatic of Mila 23 life as blue shutters and spinning wheels.

Boats are, obviously, essential to life on Mila 23, but the queen of them all is the – well here we bump into the vexed question of the difference between a canoe and a kayak. Our guide informed us that Mila 23 was a very special place for kayaks and took us to a very special museum to tell the story of a very special local man. We’ve checked and rechecked and we are pretty sure that our otherwise exceptional guide should have been talking about canoes!

The very special man was Mila 23 born Ivan Patzaichin. His father was a fisherman and his mother a dressmaker but it was his grandfather who encouraged him to try canoeing. When two other local lads won the world canoe doubles title in 1966, Ivan decided to compete as well and just two years later, he and fellow Mila 23 born Serghei Covaliov won gold at the Mexico Olympics. Patzaichin’s final medal tally was seven Olympic medals (four of which were gold) and 22 world championship medals (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ivan_Patzaichin).

Today, the Ivan Patzaichin Museum – Community Innovation Center stands tall on the Mila 23 water front and “ingeniously illustrates how natural materials traditionally used in construction, such as wood, reed, clay, and hemp, can be reinterpreted and integrated into a modern concept.” (https://muzeu.ivanpatzaichin.ro/en/museum/)

T

Meanwhile, other athletic activities continue to celebrate Lipovan culture and their love of white and blue.

Α Β Γ Δ – Greek and Romanian Geography

We’re thinking big, we’re thinking old, we’re thinking shifting, fluctuating and fluid, we’re thinking biodiverse, and internationally and politically significant. And we’re still thinking Unesco (see previous blog). Where are we?

We’re in the Danube Δelta. Sorry, we mean Delta.

Last May, we made a trip to Romania. The visit included many exciting highlights (sheep blessing, wild bears, Bran Castle - 13th century defensive Saxon castle, trading post and royal residence but cursed by the Dracula myth) and plenty more, including some of the largest wheat fields we’ve seen this side of North America. Health & Safety note: we were in a mini bus when Mamma bear appeared (cub was out of shot).

But this blog is actually about a much acclaimed and multi designated delta, a delta created by the Danube as it strolls gently across the coastal edge of eastern Europe and on into the Black Sea.

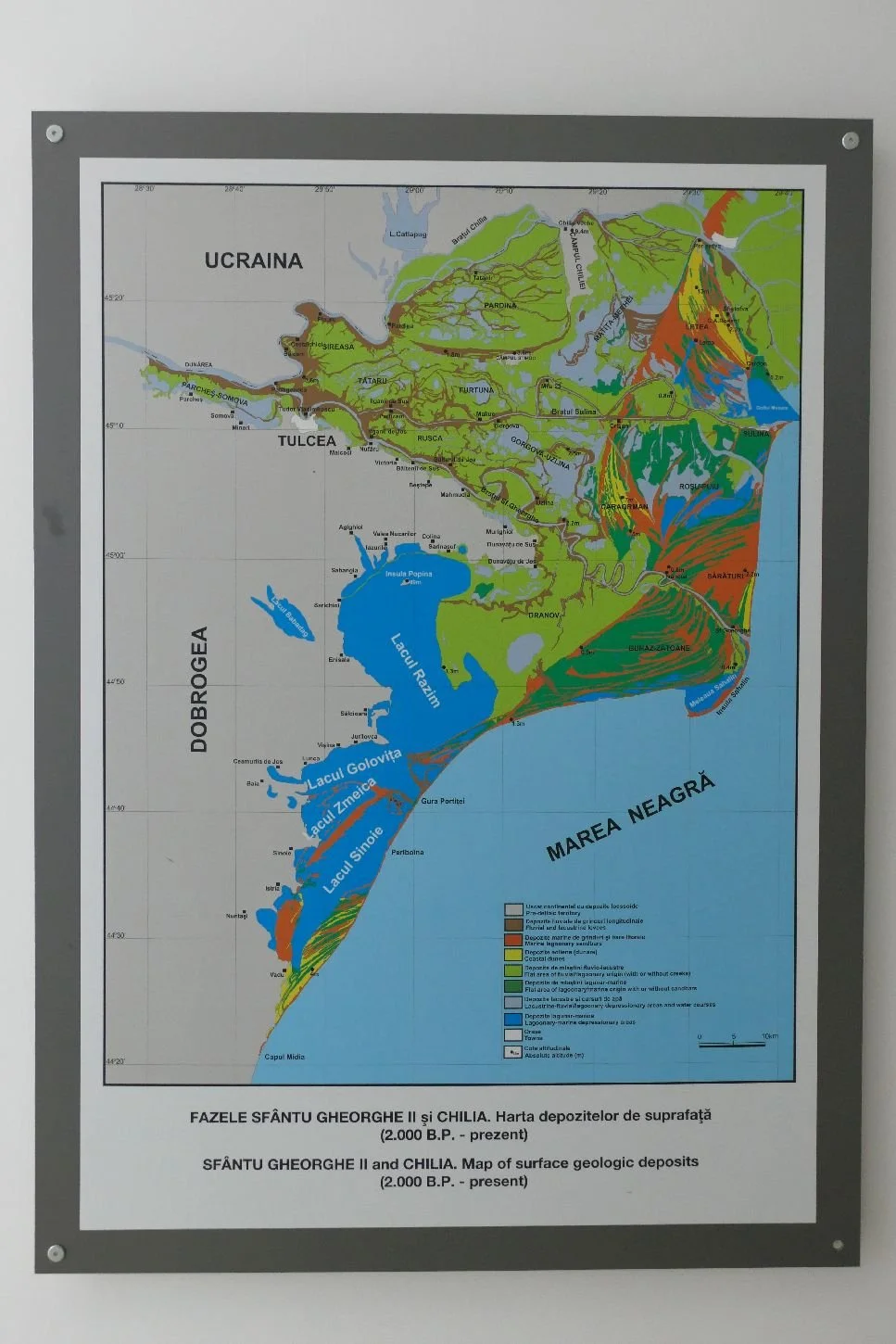

Although the Greeks are said to have invented the word ‘delta’, based on the similarity between the shape of the Nile delta and the fourth letter of the Greek alphabet, these river-created connections between land and sea come in different shapes and sizes, causing some debate over which is the ‘largest’ in the world. The Ganges is usually cited as the winner. The Danube’s delta comes first or second in Europe, depending on how you define the continent. If Europe includes south east Russia, then the Volga’s delta on the Caspian Sea takes first prize.

It’s hard to get a handle on the Danube Delta. Using Wikipedia as a source (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Danube_Delta) the overall area is 5,165 km2. In comparison, Cambridgeshire is a mere 3,389 km2. Most, but not all of those 5,000 km2 lie within Romania. And here’s the rub: some of it is in Ukraine.

Under UNESCO’s ‘Man and Biosphere Programme’, the Danube Delta was designated as a World Biosphere Reserve (WBR) in 1979 and enlarged in 1992. In 1998 it was extended into Ukraine, thus creating a significant (in biosphere terms) but more tricky (in governance terms) Transborder Reserve. If you click on the UNESCO web links to the Danube Delta WBR you get the following message: “We can’t connect to the server”. We do wonder if this is a sign of the current political situation rather than just a technical fault. Our guide for our Delta trip told us how useful drones had become in surveying the wetland ecology but that, nowadays, they can’t be used in case the drones are mistaken for missiles. The term ‘Transborder’ in this area is not just about bureaucracy.

Our guide also told us of an exciting ‘transborder’ Delta ‘Rewilding Europe’ Project (https://rewildingeurope.com/rew-project/danube-delta-rewilding-area/). Three countries are involved in this scheme: Romania, Moldova and, of course, Ukraine. Their website includes the following: “With your donation, we will be able to purchase and transfer medicine, equipment and any other priority item to cover the needs of staff, employees and their families in Ukraine.” Sadly, ecosystem support must now include the human animal as well.

We entered the world of the Delta at the port town of Tulcea which now tranships tourists as well as shipping containers. Loaded onto our tiny craft, enveloped in life jackets, we felt very small and vulnerable as we chugged along past commercial vessels which themselves were insignificant in comparison to most ocean going freighters.

Thankfully, the myriad of delta channels allows rapid reductions in scale and we were soon happily watching out for pelicans and white tailed eagles, with no vessel much bigger than ourselves in view. In that journey alone, we saw more eagles than we had ever seen before over a whole lifetime. Just the one species, mind you.

Our destination was Mila 23, once a significant location on one of the shipping routes from Tulcea to the Black Sea, and located at the 23 nautical mile marker out from the port. Today, this settlement is bypassed by commercial shipping, but has adapted well to tourism. Ourselves and our luggage were safely transferred from boat, to dock, and on into a comfortable, generously sized, family run guest house. We’ll sneak a peak in a subsequent blog.

One of us was wondering whether the delta landscape could keep us engaged and happy for the best part of four days. Team Terroir went on every available excursion, however, and never regretted a moment, even in the cold and rain. Huge thanks are due to our extremely knowledgeable guide who had left a probably much more lucrative career as a lawyer to engage full time in the conservation and interpretation of this extraordinary piece of world ‘biosphere’.

The bird life is spectacular, of course. The conjunction of water and land will always provide a richness of habitat for both flora and fauna but this extensive area of slow flowing delta, with many channels of varying depth and width, is particularly magical, especially with a knowledgeable guide with sharp eyesight and good ear for bird song.

Pelicans are the initial show stoppers. They are easy to spot, of course, being striking in their size (and this includes their feet), their idiosyncratic bills, their ability to look like flying mushrooms when surfing the thermals, and their ability to cooperate with other species such as cormorants (above right). The collective nouns which we humans have applied (squadron, pod, pouch and scoop) go some way to describe their life style.

Eventually, our bird count reached well over 40 species, including many familiar faces such as swallows, grey herons, mute swans, black headed gulls and greylag geese (right). Many, such as whiskered terns, some glossy ibis and a bearded tit refused to be caught on camera, but a few (below) were coaxed into posing for the camera.

Images above and right © Brett Halliday

This somewhat hasty shot of a cuckoo was particularly special to a crew of British tourists who, these days, seldom hear the once iconic song of an English summer. This individual cooed to us for several hours as we toured the delta waterways.

Its not just birds of course. Fish, amphibians, invertebrates of all sorts, reptiles and mammals abound but are harder to see and even harder to photograph. Some amphibians were very noisy, however, and these little critters (below left) were very active during our springtime visit. The North American muskrat was introduced to Europe in the early 20th century and is no stranger to the Danube delta. The native otter has had a harder struggle but seems to be spreading after a programme of re-introduction. We think the chap below right is a muskrat but would be happy to be corrected.

The more terrestrial landscape is also worth a look, although harder to see from water level. At first glance the water’s edge seems to be a flexible, undulating, but remarkably dense barrier of Common Reed (Phragmites australis) although it grows to such proportions that you can’t help worrying that Giant Reed (a hugely invasive pest in much of Europe) has started to colonise.

A quick web search hinted that the Giant Reed might have already been found in the Ukrainian part of the delta. Can anyone update us?

This giant reed threat is just one example of the changeable relationship between open water and land habitats. The economics of water transport has altered hugely with the introduction of aspects such as containerisation and the need for larger ocean-going vessels. Dredging and creation of more direct routes to the sea have not only meant that places like Mila 23 are now bypassed by commercial shipping, but more significantly, meant a drop in the delta’s water levels and increased colonisation by woody species. The tree is the enemy!

Let’s take a look back and see how the humans adapted to enable existence in this wetland ecosystem. Reed was the mainstay for the traditional delta communities and was used for fodder, fuel, thatch, fencing, construction and decorative purposes. Increased urbanisation and industrialisation means that demand for this crop is now severely reduced but, as we will see, some traditional management practices die hard!

We were curious about the number of burnt trees along the channel edges (see above) and were told that it was a tradition from former times. Reed and any sneaky tree species were burned to maximise the reed crop to provide its most appropriate age and size for whatever end product was required. We were told that tree burning still occurs despite the current low demand for the reed. There was a distinct impression that burning continues (see above) as an attractive pass time for the younger (males?) in the local communities!

Today, the wetland delta habitat presents a variety of ecological niches. It is a network of open water, of wide and narrow channels, of varying depths, of varying accessibility (especially if you don’t have a boat!), of varying uses and varying options according to the varying weather and varying seasons.

Water chestnut, yellow water lily and blue lotus (left to right above) love the shallows. Below, small boats love the myriad of creeks and open water bodies, which guaranteed we never really know where we were! Thankfully, our guide always knew where to look for something special, and how to get us home.

Our journey to the Danube Delta (and there will be more about this trip in our next blog) owes special thanks to some special people: Brett Halliday for allowing us to share some of his spectacular photographs; to Ramona and Dan at MyRomania (https://myromania.ro/) who can craft pretty much any type of trip to Romania, and to the people at Ffestiniog Travel (https://www.ffestiniogtravel.com/) who commissioned this particular visit. Thank you.

It’s all Arkwright

How many UNESCO World Heritage Sites are there in the UK?

It seems that there are 20 in England (the City of Bath seems to count as two sites), 6 in Scotland, 7 in Wales, and 2 in Northern Ireland. This might seem like a small number, suggesting that UK heritage isn’t of much value on the global stage. To become a World Heritage Site, however, one must apply/be nominated and the process isn’t a walk in the park - it makes an application for funding to the UK National Lottery funds look like a teddy bear’s picnic in comparison.

“To be included on the World Heritage List, sites must be of outstanding universal value and meet at least one out of ten selection criteria.” (https://whc.unesco.org/en/criteria/). These criteria include both cultural and natural aspects. Examples include representing a masterpiece of human creative genius, bearing a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition, or containing superlative natural phenomena or areas of exceptional natural beauty and aesthetic importance.

UK sites which have chosen to go through the process, and come out successful, include the Flow Country, and the Antonine Wall in Scotland, Moravian Church Settlements: Gracehill in Northern Ireland, The Jurassic Coast, Saltaire, and Maritime Greewich in England, and the Slate Landscape of North West Wales, and the Blaenavon Industrial Landscape, in South Wales.

Imagine our surprise, therefore, when our explorations of the High, Dark and White aspects of the Peak District National Park (see previous two blogs) brought us up close and personal with another of England’s World Heritage Sites: the Derwent Valley Mills.

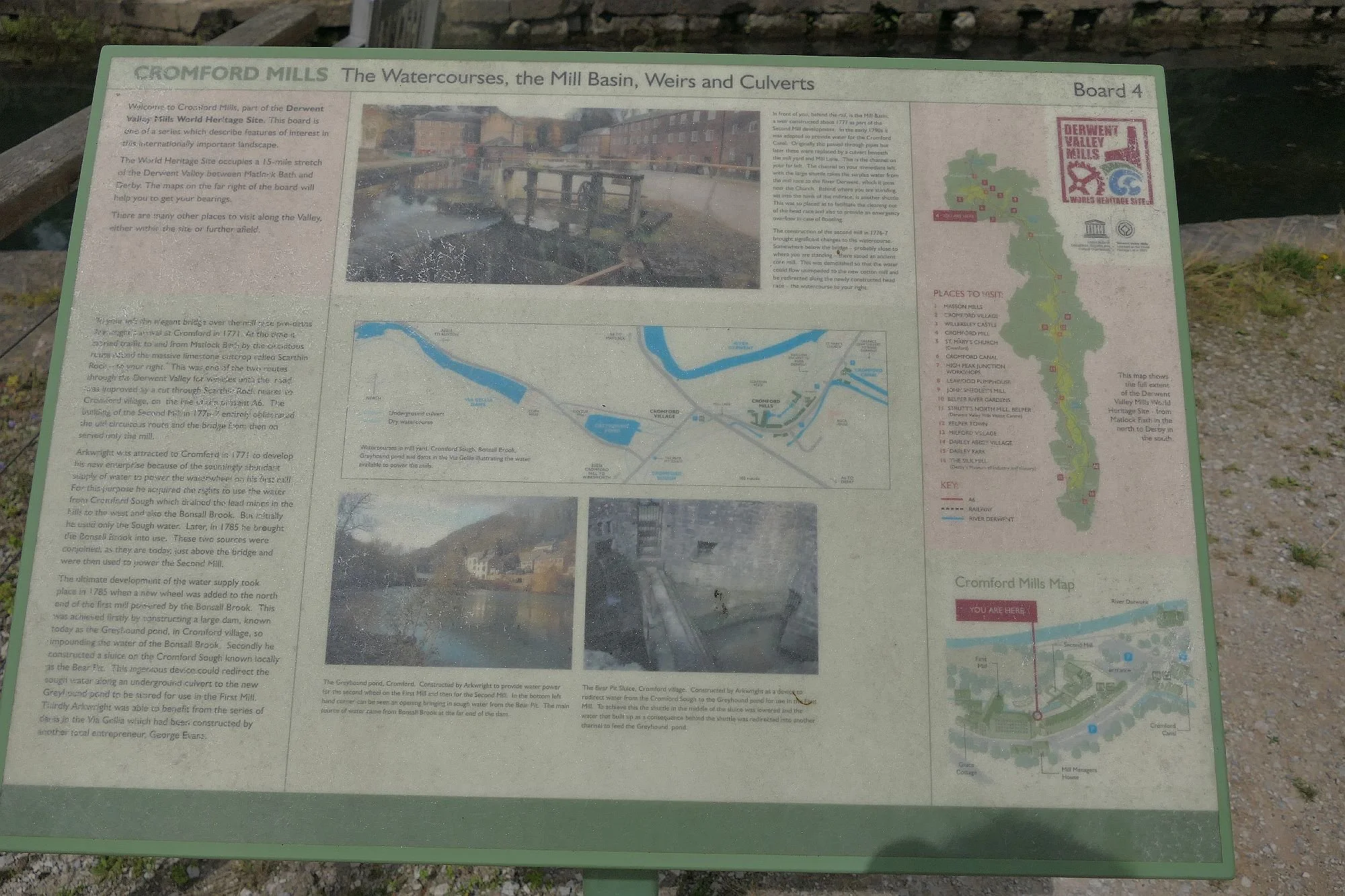

Regular readers will be aware that we have been exploring the history of Peak District terminology and were particularly puzzled by the term ‘High Peak’ which seemed to be applied, somewhat carelessly perhaps, to many very different parts of Derbyshire, both Dark and White. Having explored the Dark Peak in our previous blog we felt the need to go south and investigate High Peak Junction (in White Peak country) where the late 18th century Cromford Canal met the early 19th century Cromford and High Peak Railway. What innocents we were! We will tell our story in order of historical chronology, despite our actual foray jumping about the centuries in as confusing a way as the geography of the so called Derbyshire ‘High Peak’.

Let us introduce you to Richard Arkwright, the barber of Bolton. Arkwright was born in Preston in 1732, was taught to read and write by his cousin Ellen (school was too expensive) and apprenticed to a barber, later setting up his own business as a barber and wig maker in Bolton. Here he is said to have invented a waterproof dye (as you do) for gentlemen’s periwigs. By 1868 he was working with a clockmaker, and the combination of wigs and mechanics seems to have created the dream team to invent a new sort of spinning machine. “This machine, initially powered by horses … greatly reduced the cost of cotton-spinning, and would lead to major changes in the textile industry.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Arkwright).

Add improvements to Lewis Paul’s carding machine and a business partner (John Smalley), and a horse driven textile factory is set up in Nottingham. Add more capital via more business partners with a side helping of bitterly disputed patent proceedings and by 1771, Arkwright is building a mega mill on the River Derwent in Cromford, Derbyshire. He went on to establish many other mills in Derbyshire and Lancashire and was also involved in New Lanark mills on the Clyde to the south east of Glasgow.

At Cromford, the powerful, imposing and rather grim mill buildings surround a courtyard which, today, is a somewhat bleak setting for the visitor-oriented craft and book shops, and its elderly and hard-to-read interpretation panels. In its heyday both mills and yard must have been noisy, frantic, forbidding and perhaps terrifying spaces for those who worked there.

On Arkwright’s heels came other entrepreneurs, eager to exploit the energy potential of the Derwent. Manufacturing spread along the valley, from Matlock to the north, through Cromford, and on to Belper, Milford, Darley Abbey and Derby. Things were never the same again – until textile production moved to major cities. “Derwent Valley slowed leaving the area ‘suspended in time’. The landscape remains much as it did in the 1800s with the mills, waterways, housing and canals inserted into a rural landscape of farmland and woodland.” (https://unesco.org.uk/our-sites/world-heritage-sites/derwent-valley-mills)

During the good times, however, and considering the level of production emanating from the Derwent valley in its prime, it was not surprising that an alternative form of transport was also required to augment and replace the horse and cart. By 1779, the Erewash Canal had been built, connecting southern Derbyshire to the River Trent, south west of Nottingham. By 1794, the Cromford canal had also been constructed to link the Derwent valley mills to the Erewash and Nottingham canals.

As part of our visit, Terroir walked the final section of the Cromford canal from its terminus at Arkwright’s Mills to High Peak Junction, of which more in a minute. The canal is still technically navigable here although the only craft we saw was the tourist boat and a collection of young paddle boarders. The tow path provides an accessible terrain which makes an attractive canal side walk for all ages and abilities. Cyclists are politely asked to give way to pedestrians.

The tow path (canal bank one side and a drop to woodland on the other) also provides a clear indication that we are in the White Peak not the Dark. Damp and limestone tolerant plants were everywhere.

Arriving at High Peak Junction we were introduced to the 19th century transport revolution which would kill the canals. This was, of course, the railways: meeting the needs of the industrial revolution in a way that horses – or even Arkwright’s use of water – could never do. The Cromford and High Peak Railway (CHPR), from Whaley Bridge to Cromford, was opened in 1831, less than 40 years after the Cromford Canal’s construction, and only 6 years after the Stockton and Darlington Railway (SDR), the 200th anniversary of which we are celebrating this year.

Being such an early railway company, many aspects of technology were also still developing. The CHPR could reduce canal haulage times by 50%, but that actually meant that a four day journey became reduced to - two days! This ‘improvement’ still sounds extraordinarily slow, but we’re talking Peak District transport and the railway’s route included a number of steep inclines. The canal went round the hills, hence the four day’s trip. The railway trucks went over the hills, using a kind of mixed transist sytem with steam locomotives on the flatter bits and horses or a static steam engine on the steep uphill inclines, while gravity took care of the downhill sections.

Right: The incline cominginto Cromford and High Peak Junction

On the downhill journey into High Peak Junction, a catch pit was inserted between the two sets of tracks on the incline, to trap any run away wagon (see diagram below left). If the wagons were descending in a controlled manner, they were swiched onto the bypass line and allowed to run into the yard under their own momentum. A run away truck, however, would be kept on the central line to be caught by the catch pit, thus preventing damage to other trucks and the yard.

The railway workforce must have been a very different crew to those working in the mills. Mill engineers would of course have been required to keep the water wheels turning and the machinery running but their contribution seems to have been overwhelmed by the massive labour force who tended the spinning machines. In contrast, the CHPR workshop museum at Cromford and High Peak Junction is a testament to the range of skilled craftspeople who kept the railway running.

All these elements – Arkwright’s Mills, the canal and the railway line – are constituents of the Derwent Valley World Heritage Site and all were a part of the industrial revolution which the River Derwent supported. The mill site clearly celebrates Arkwright and his revolutionary engineering and entrepreneurial achievements, from bigger and better spinning machines to harnessing water power and person power, to enable bigger and more productive cotton mills. For Terroir, however, the ‘Miller’s Tale’ neglects the story of all the other people who worked at the Mill, from single men and women to entire families, people who worked 12 hour days for 51 weeks of the year. Perhaps another visit, to other Mills within the valley Heritage Site, do tell that story. We will try to report back another time.

Summer Guide to Derbyshire - the Dark Peak

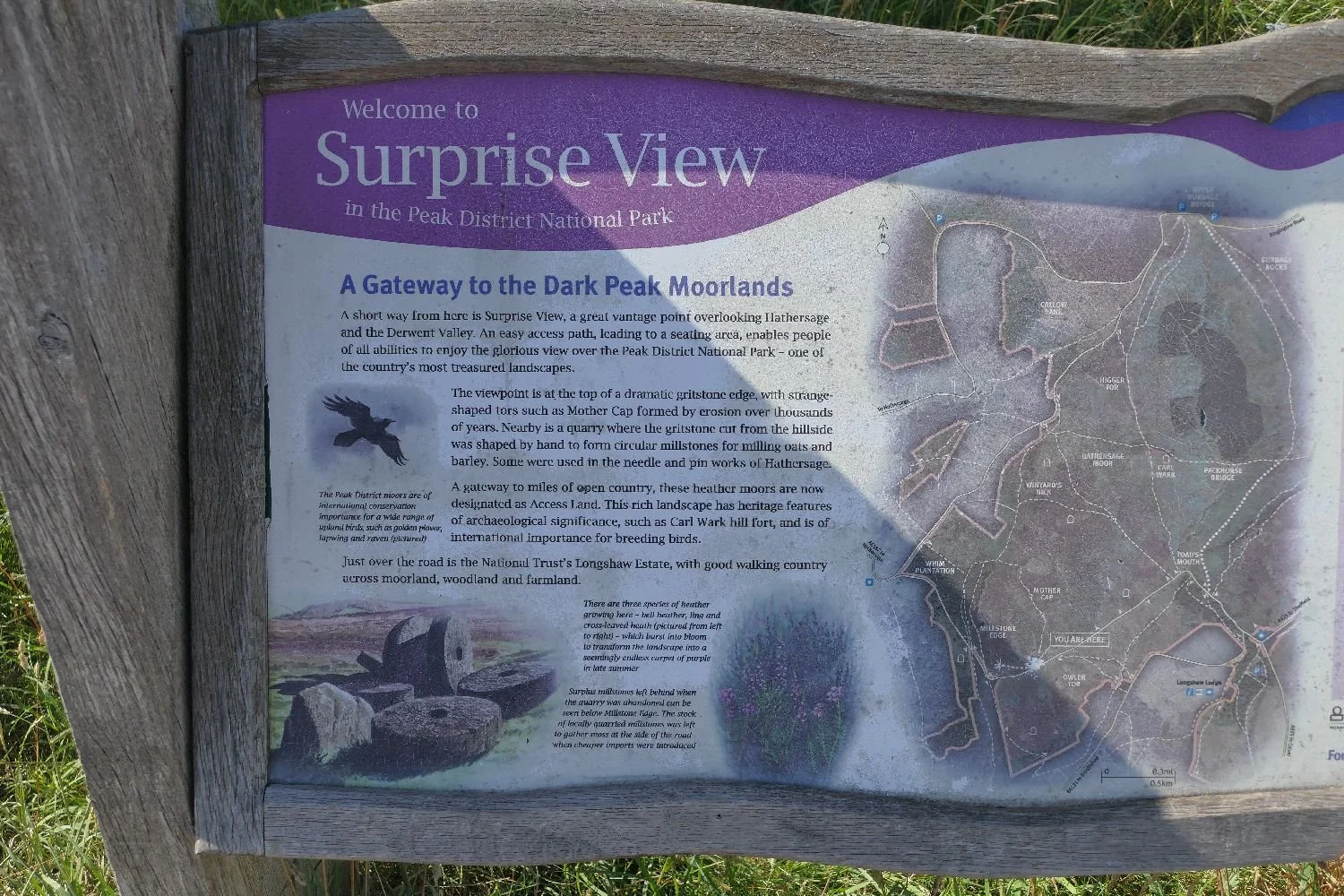

Last January we reported back on a Christmas in the Peak District, viewed through the Boomer generation’s lens of Ladybird Books. Six months later we returned to find that summer was shining a light on the mystery of the ‘Dark Peak’.

These days everyone seems to refer to the Peak District in terms of the White Peak (the cavernous and craggy limestone area between Buxton, Matlock, Leek and Ashbourne) and the Dark Peak – the gritstones between Sheffield and Manchester - and described by various sources as higher, wetter and more acidic than its White Peak counterpart.

Terroir has no memory of the Peak District having any such names in our childhood or early adulthood. References to the High Peak, however do feel familiar and appear to be enshrined in a sufficiency of locations to be applicable anywhere in the Peak District! A digression, we admit, but we present the following as evidence:

High Peak Parliamentary Constituency - currently represented by Labour MP John Pearce and largely but by no means exclusively a millstone grit landscape.

High Peak Borough Council “covering a high moorland plateau in the Dark Peak area of the Peak District National Park” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High_Peak,_Derbyshire)

High Peak Junction on the Cromford Canal (built 1794) which may have given its name to the Cromford and High Peak Railway (1831 – 1967) “built to carry minerals and goods through the hilly rural terrain of the Peak District within Derbyshire” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cromford_and_High_Peak_Railway).

Much of the track bed has now been converted into the High Peak Trail, which appears to be more of a White Peak than Dark Peak facility.

End of digression!

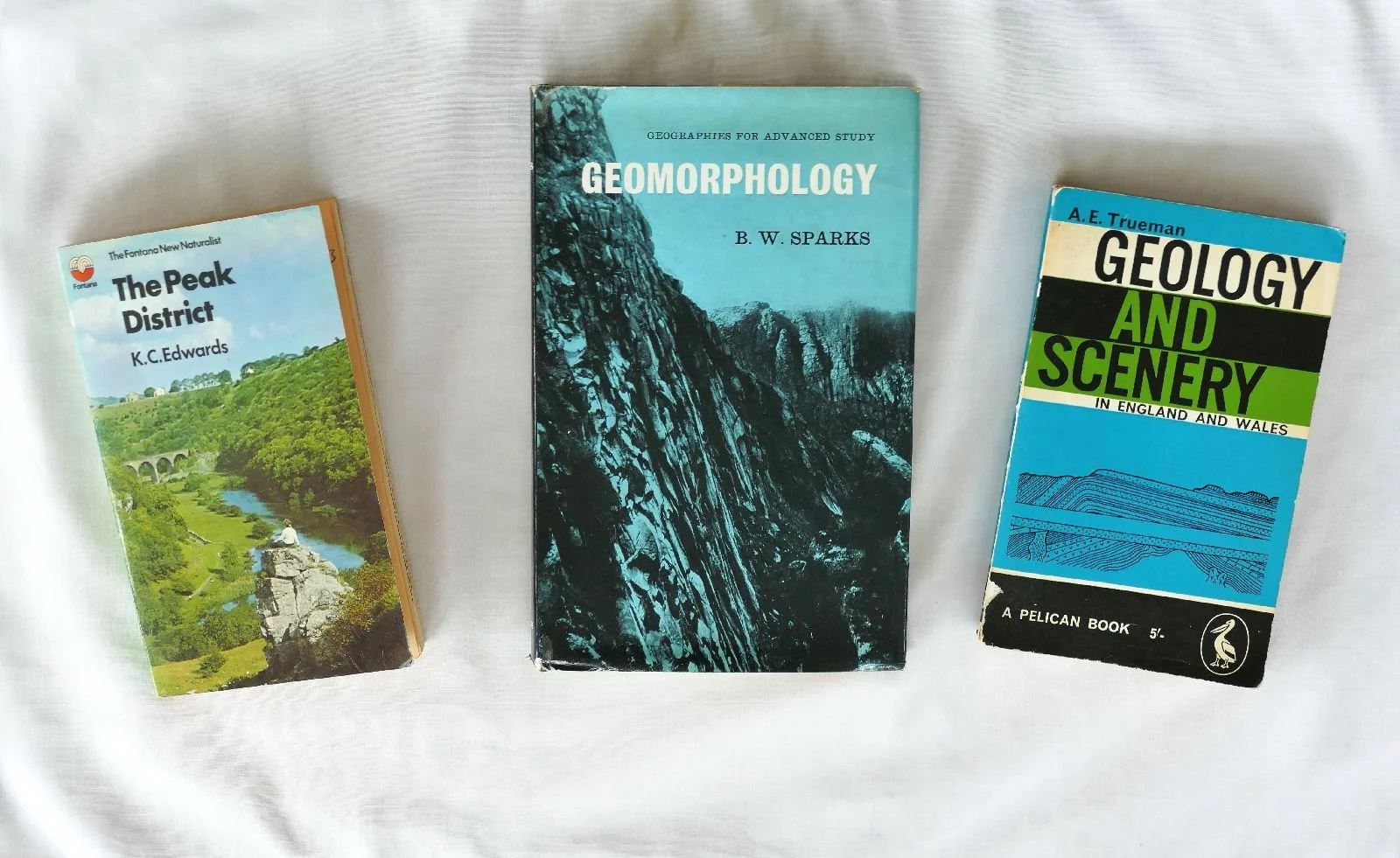

To research the origin of the name ‘Dark Peak’ we resorted to a number of elderly volumes, gathering dust on our bookshelves. The oldest is AE Trueman’s “Geology and Scenery in England and Wales”, a much loved companion to my early years. First published in 1938, a Pelican edition arrived in 1949. There is not a single mention of the Dark Peak but (digression alert) Trueman comments that “Another great area of Mountain Limestone forms the High Peak, the most southerly part of the Pennines”. We give up!

Next is B W Sparks’ “Geomorphology” (published 1960), a slightly dry companion to university years (belonging, as it does, to a series called “Geographies for Advanced Studies”). I suppose it was never going to be a bundle of laughs and it was too light on matters of landscape to be a boon companion. There is no mention of the Peak District as such, or of Millstone grit. Under ‘Limestone Relief’ there is a brief reference to Malham Tarn but examples in France and Yugoslavia quickly take priority.

How many readers remember the green covers of the New Naturalist series? First published in 1962, the Fontana paperback came out in 1973 (our copy of the same year is inscribed as ‘a birthday present from Auntie Rene’). It consists of 225 closely printed pages but no indexed reference to either the Dark or the White Peak.

In desperation we ask Chatgpt. Here is a summary of the responses: