Summer Guide to Derbyshire - the Dark Peak

Last January we reported back on a Christmas in the Peak District, viewed through the Boomer generation’s lens of Ladybird Books. Six months later we returned to find that summer was shining a light on the mystery of the ‘Dark Peak’.

These days everyone seems to refer to the Peak District in terms of the White Peak (the cavernous and craggy limestone area between Buxton, Matlock, Leek and Ashbourne) and the Dark Peak – the gritstones between Sheffield and Manchester - and described by various sources as higher, wetter and more acidic than its White Peak counterpart.

Terroir has no memory of the Peak District having any such names in our childhood or early adulthood. References to the High Peak, however do feel familiar and appear to be enshrined in a sufficiency of locations to be applicable anywhere in the Peak District! A digression, we admit, but we present the following as evidence:

High Peak Parliamentary Constituency - currently represented by Labour MP John Pearce and largely but by no means exclusively a millstone grit landscape.

High Peak Borough Council “covering a high moorland plateau in the Dark Peak area of the Peak District National Park” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/High_Peak,_Derbyshire)

High Peak Junction on the Cromford Canal (built 1794) which may have given its name to the Cromford and High Peak Railway (1831 – 1967) “built to carry minerals and goods through the hilly rural terrain of the Peak District within Derbyshire” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cromford_and_High_Peak_Railway).

Much of the track bed has now been converted into the High Peak Trail, which appears to be more of a White Peak than Dark Peak facility.

End of digression!

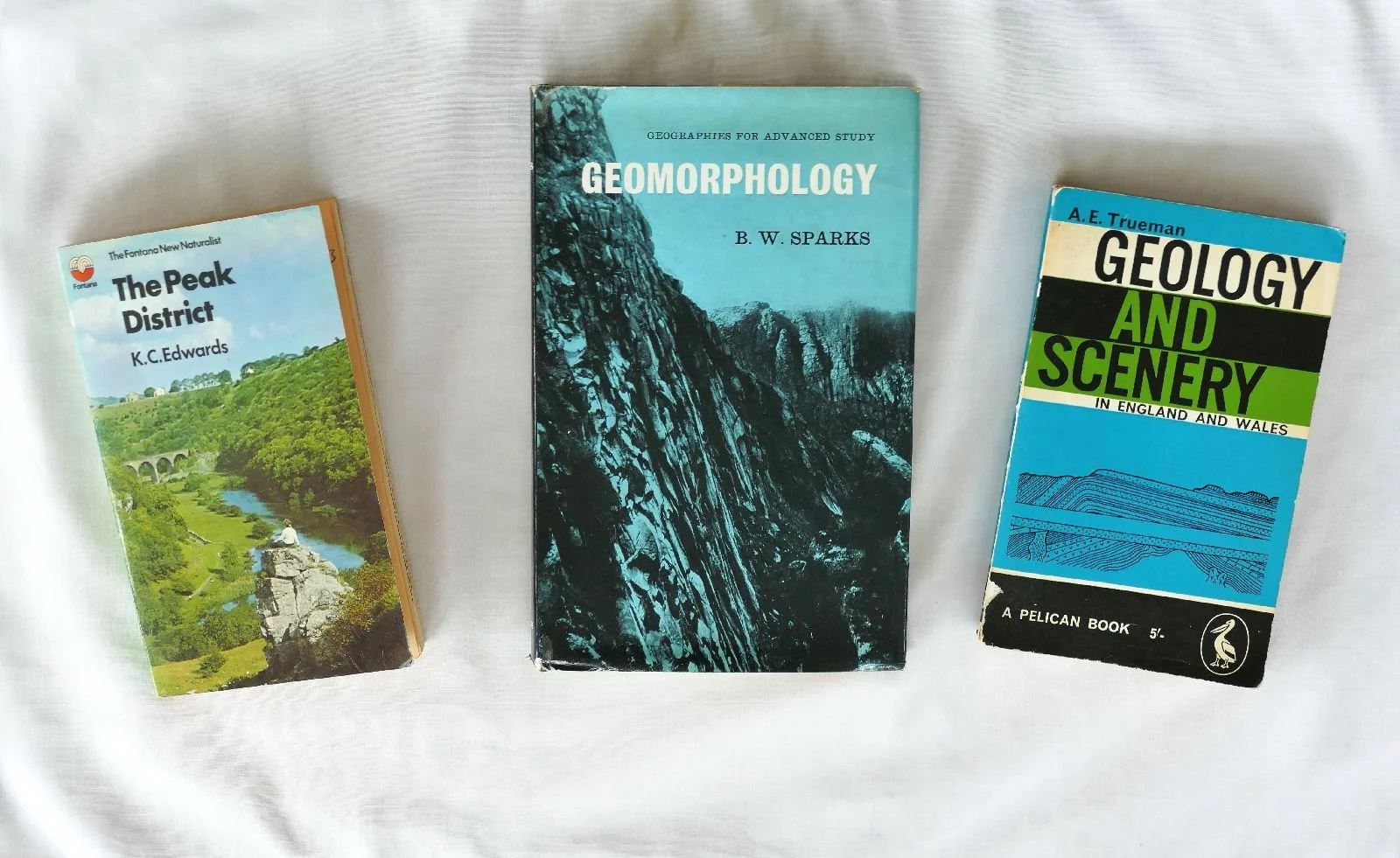

To research the origin of the name ‘Dark Peak’ we resorted to a number of elderly volumes, gathering dust on our bookshelves. The oldest is AE Trueman’s “Geology and Scenery in England and Wales”, a much loved companion to my early years. First published in 1938, a Pelican edition arrived in 1949. There is not a single mention of the Dark Peak but (digression alert) Trueman comments that “Another great area of Mountain Limestone forms the High Peak, the most southerly part of the Pennines”. We give up!

Next is B W Sparks’ “Geomorphology” (published 1960), a slightly dry companion to university years (belonging, as it does, to a series called “Geographies for Advanced Studies”). I suppose it was never going to be a bundle of laughs and it was too light on matters of landscape to be a boon companion. There is no mention of the Peak District as such, or of Millstone grit. Under ‘Limestone Relief’ there is a brief reference to Malham Tarn but examples in France and Yugoslavia quickly take priority.

How many readers remember the green covers of the New Naturalist series? First published in 1962, the Fontana paperback came out in 1973 (our copy of the same year is inscribed as ‘a birthday present from Auntie Rene’). It consists of 225 closely printed pages but no indexed reference to either the Dark or the White Peak.

In desperation we ask Chatgpt. Here is a summary of the responses:

“The term appears in official geological and topographical surveys by the early 1900s”.

And:

“No specific first printed mention is readily indexed online, but the terminology is believed to date from the early 1900s, particularly in publications aimed at walkers and naturalists.”

In other words nobody has bothered to digitise any of this material so Chatgpt is entirely ignorant of its contents. So much for AI.

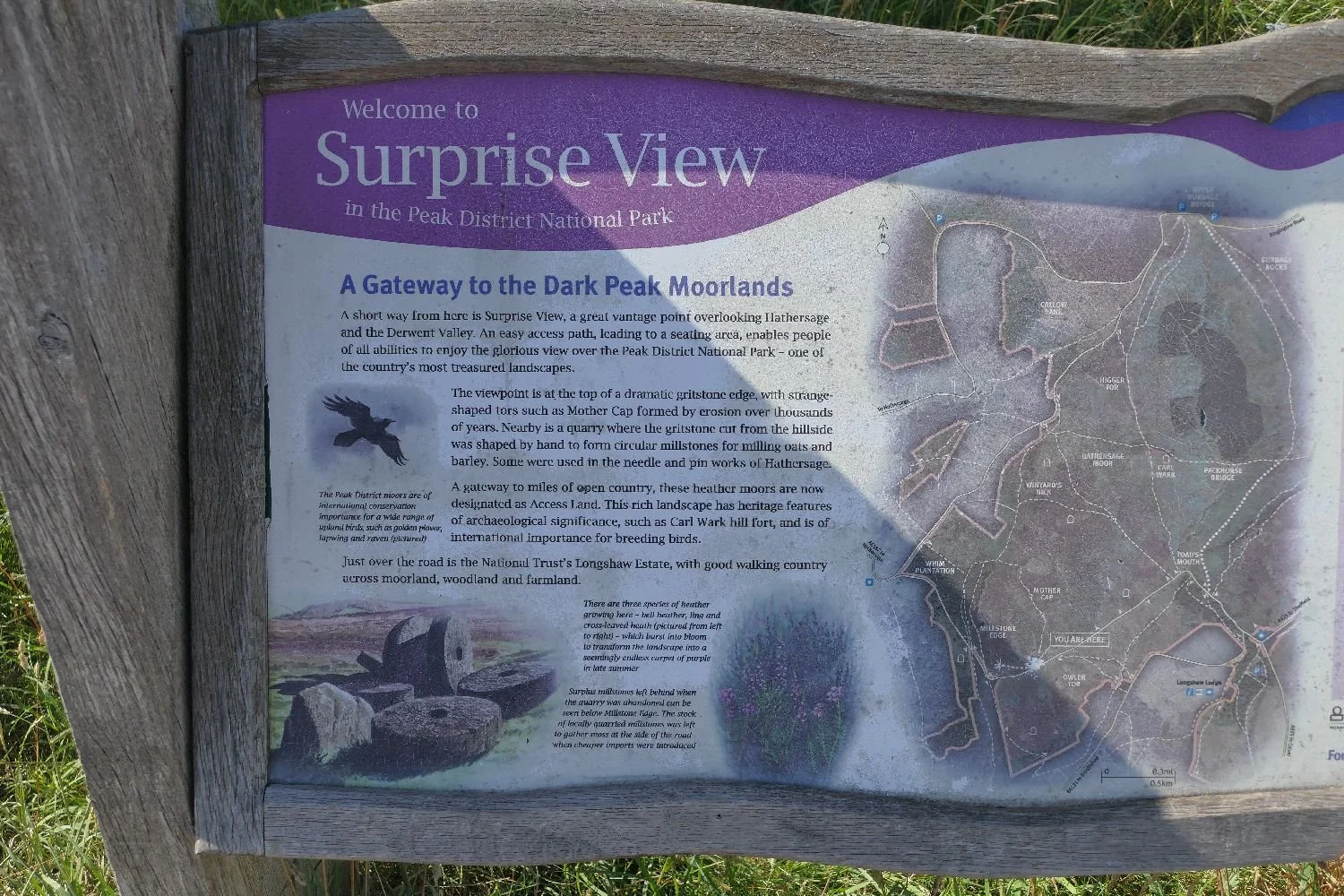

To Terroir, the Dark Peak sounds like something out of a Sci Fi film, but that doesn’t sit well with either the Ladybird Book image from last Christmas or those who promote the area for health and well-being and for tourism. So here is Terroir’s friendly, picture book guide to the totally benign and utterly un-scary Daaaark Peak. Welcome to Surprise View!

Eerie open moorland and stern blocks of Millstone Grit are tempered by clumps of birch trees and heather. Note the non-traditional post and wire Dark Peak fencing which allows a spooky, even-aged stand of birch to grow unmolested by grazing sheep.

Spiny spear thistle and fearsome foxgloves keep the very wild wildlife focused on nectar while lichen lurks on sign posts to ensure a quick getaway, if need be.

Heather comes in three varieties: from left to right - well tempered cross leaved heath, the massed ranks of Ling and bright clumps of bell heather.

Starvation can be staved off with bilberries, cowberries and the Longshaw National Trust cafe. Longshaw recently hosted BBC Spring Watch, with plenty of dark photography but no apparent mishaps amongst presenters and crew.

Plenty of other spooky destinations (this is Stanton Moor) are avalable.

The Ladybird Book of the BLack Peak is long overdue.