It’s all Arkwright

How many UNESCO World Heritage Sites are there in the UK?

It seems that there are 20 in England (the City of Bath seems to count as two sites), 6 in Scotland, 7 in Wales, and 2 in Northern Ireland. This might seem like a small number, suggesting that UK heritage isn’t of much value on the global stage. To become a World Heritage Site, however, one must apply/be nominated and the process isn’t a walk in the park - it makes an application for funding to the UK National Lottery funds look like a teddy bear’s picnic in comparison.

“To be included on the World Heritage List, sites must be of outstanding universal value and meet at least one out of ten selection criteria.” (https://whc.unesco.org/en/criteria/). These criteria include both cultural and natural aspects. Examples include representing a masterpiece of human creative genius, bearing a unique or at least exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition, or containing superlative natural phenomena or areas of exceptional natural beauty and aesthetic importance.

UK sites which have chosen to go through the process, and come out successful, include the Flow Country, and the Antonine Wall in Scotland, Moravian Church Settlements: Gracehill in Northern Ireland, The Jurassic Coast, Saltaire, and Maritime Greewich in England, and the Slate Landscape of North West Wales, and the Blaenavon Industrial Landscape, in South Wales.

Imagine our surprise, therefore, when our explorations of the High, Dark and White aspects of the Peak District National Park (see previous two blogs) brought us up close and personal with another of England’s World Heritage Sites: the Derwent Valley Mills.

Regular readers will be aware that we have been exploring the history of Peak District terminology and were particularly puzzled by the term ‘High Peak’ which seemed to be applied, somewhat carelessly perhaps, to many very different parts of Derbyshire, both Dark and White. Having explored the Dark Peak in our previous blog we felt the need to go south and investigate High Peak Junction (in White Peak country) where the late 18th century Cromford Canal met the early 19th century Cromford and High Peak Railway. What innocents we were! We will tell our story in order of historical chronology, despite our actual foray jumping about the centuries in as confusing a way as the geography of the so called Derbyshire ‘High Peak’.

Let us introduce you to Richard Arkwright, the barber of Bolton. Arkwright was born in Preston in 1732, was taught to read and write by his cousin Ellen (school was too expensive) and apprenticed to a barber, later setting up his own business as a barber and wig maker in Bolton. Here he is said to have invented a waterproof dye (as you do) for gentlemen’s periwigs. By 1868 he was working with a clockmaker, and the combination of wigs and mechanics seems to have created the dream team to invent a new sort of spinning machine. “This machine, initially powered by horses … greatly reduced the cost of cotton-spinning, and would lead to major changes in the textile industry.” (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Arkwright).

Add improvements to Lewis Paul’s carding machine and a business partner (John Smalley), and a horse driven textile factory is set up in Nottingham. Add more capital via more business partners with a side helping of bitterly disputed patent proceedings and by 1771, Arkwright is building a mega mill on the River Derwent in Cromford, Derbyshire. He went on to establish many other mills in Derbyshire and Lancashire and was also involved in New Lanark mills on the Clyde to the south east of Glasgow.

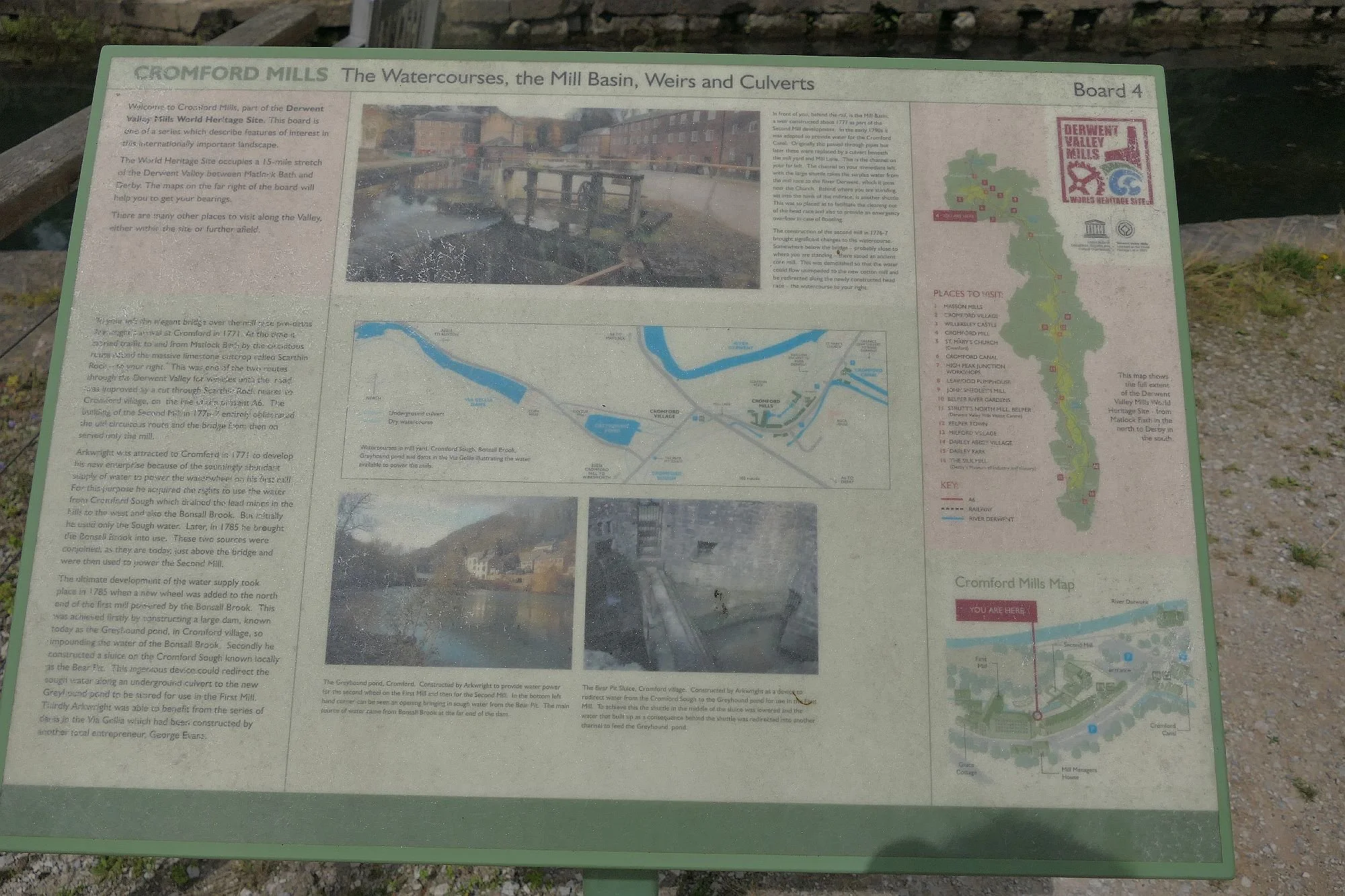

At Cromford, the powerful, imposing and rather grim mill buildings surround a courtyard which, today, is a somewhat bleak setting for the visitor-oriented craft and book shops, and its elderly and hard-to-read interpretation panels. In its heyday both mills and yard must have been noisy, frantic, forbidding and perhaps terrifying spaces for those who worked there.

On Arkwright’s heels came other entrepreneurs, eager to exploit the energy potential of the Derwent. Manufacturing spread along the valley, from Matlock to the north, through Cromford, and on to Belper, Milford, Darley Abbey and Derby. Things were never the same again – until textile production moved to major cities. “Derwent Valley slowed leaving the area ‘suspended in time’. The landscape remains much as it did in the 1800s with the mills, waterways, housing and canals inserted into a rural landscape of farmland and woodland.” (https://unesco.org.uk/our-sites/world-heritage-sites/derwent-valley-mills)

During the good times, however, and considering the level of production emanating from the Derwent valley in its prime, it was not surprising that an alternative form of transport was also required to augment and replace the horse and cart. By 1779, the Erewash Canal had been built, connecting southern Derbyshire to the River Trent, south west of Nottingham. By 1794, the Cromford canal had also been constructed to link the Derwent valley mills to the Erewash and Nottingham canals.

As part of our visit, Terroir walked the final section of the Cromford canal from its terminus at Arkwright’s Mills to High Peak Junction, of which more in a minute. The canal is still technically navigable here although the only craft we saw was the tourist boat and a collection of young paddle boarders. The tow path provides an accessible terrain which makes an attractive canal side walk for all ages and abilities. Cyclists are politely asked to give way to pedestrians.

The tow path (canal bank one side and a drop to woodland on the other) also provides a clear indication that we are in the White Peak not the Dark. Damp and limestone tolerant plants were everywhere.

Arriving at High Peak Junction we were introduced to the 19th century transport revolution which would kill the canals. This was, of course, the railways: meeting the needs of the industrial revolution in a way that horses – or even Arkwright’s use of water – could never do. The Cromford and High Peak Railway (CHPR), from Whaley Bridge to Cromford, was opened in 1831, less than 40 years after the Cromford Canal’s construction, and only 6 years after the Stockton and Darlington Railway (SDR), the 200th anniversary of which we are celebrating this year.

Being such an early railway company, many aspects of technology were also still developing. The CHPR could reduce canal haulage times by 50%, but that actually meant that a four day journey became reduced to - two days! This ‘improvement’ still sounds extraordinarily slow, but we’re talking Peak District transport and the railway’s route included a number of steep inclines. The canal went round the hills, hence the four day’s trip. The railway trucks went over the hills, using a kind of mixed transist sytem with steam locomotives on the flatter bits and horses or a static steam engine on the steep uphill inclines, while gravity took care of the downhill sections.

Right: The incline cominginto Cromford and High Peak Junction

On the downhill journey into High Peak Junction, a catch pit was inserted between the two sets of tracks on the incline, to trap any run away wagon (see diagram below left). If the wagons were descending in a controlled manner, they were swiched onto the bypass line and allowed to run into the yard under their own momentum. A run away truck, however, would be kept on the central line to be caught by the catch pit, thus preventing damage to other trucks and the yard.

The railway workforce must have been a very different crew to those working in the mills. Mill engineers would of course have been required to keep the water wheels turning and the machinery running but their contribution seems to have been overwhelmed by the massive labour force who tended the spinning machines. In contrast, the CHPR workshop museum at Cromford and High Peak Junction is a testament to the range of skilled craftspeople who kept the railway running.

All these elements – Arkwright’s Mills, the canal and the railway line – are constituents of the Derwent Valley World Heritage Site and all were a part of the industrial revolution which the River Derwent supported. The mill site clearly celebrates Arkwright and his revolutionary engineering and entrepreneurial achievements, from bigger and better spinning machines to harnessing water power and person power, to enable bigger and more productive cotton mills. For Terroir, however, the ‘Miller’s Tale’ neglects the story of all the other people who worked at the Mill, from single men and women to entire families, people who worked 12 hour days for 51 weeks of the year. Perhaps another visit, to other Mills within the valley Heritage Site, do tell that story. We will try to report back another time.