Α Β Γ Δ – Greek and Romanian Geography

We’re thinking big, we’re thinking old, we’re thinking shifting, fluctuating and fluid, we’re thinking biodiverse, and internationally and politically significant. And we’re still thinking Unesco (see previous blog). Where are we?

We’re in the Danube Δelta. Sorry, we mean Delta.

Last May, we made a trip to Romania. The visit included many exciting highlights (sheep blessing, wild bears, Bran Castle - 13th century defensive Saxon castle, trading post and royal residence but cursed by the Dracula myth) and plenty more, including some of the largest wheat fields we’ve seen this side of North America. Health & Safety note: we were in a mini bus when Mamma bear appeared (cub was out of shot).

But this blog is actually about a much acclaimed and multi designated delta, a delta created by the Danube as it strolls gently across the coastal edge of eastern Europe and on into the Black Sea.

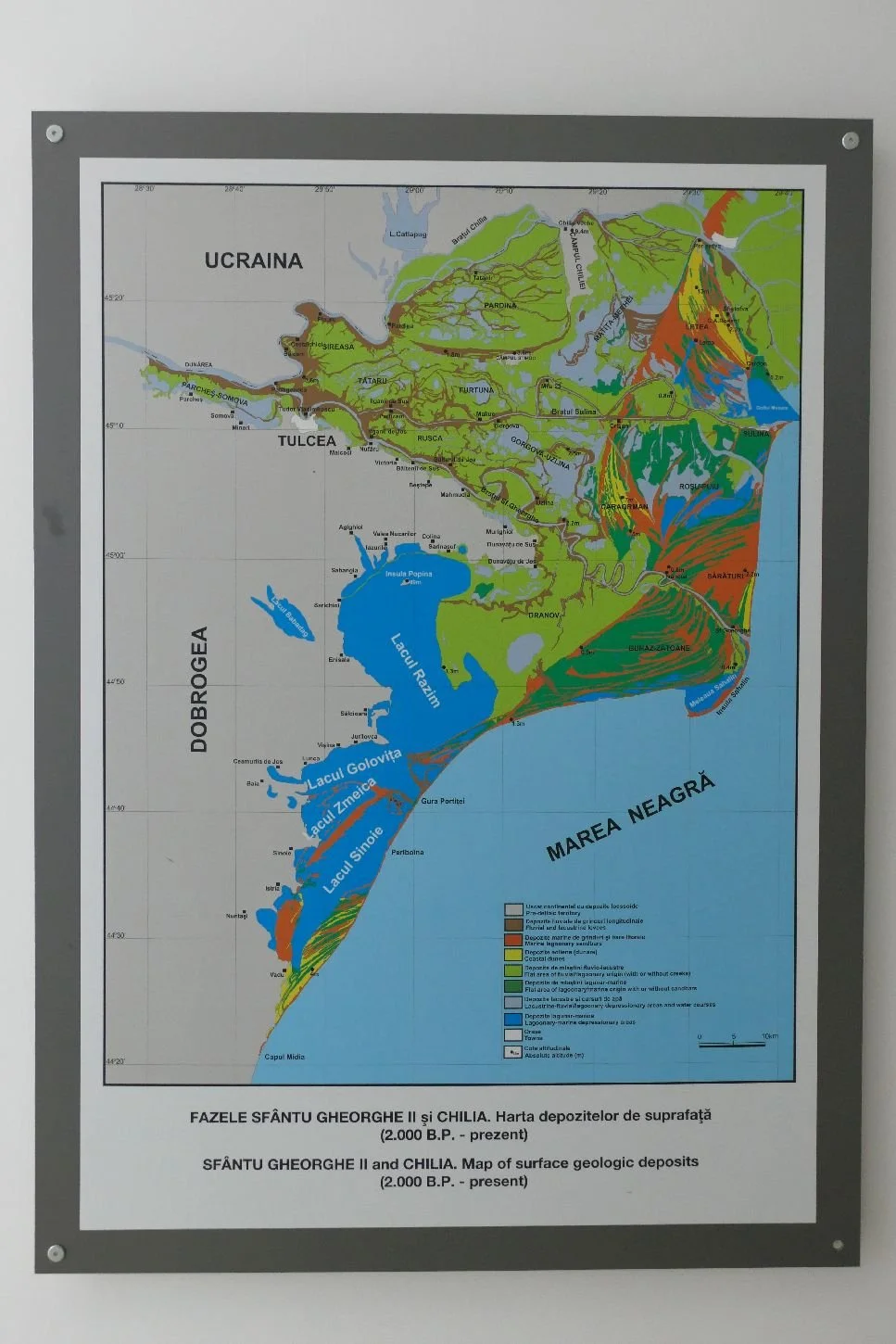

Although the Greeks are said to have invented the word ‘delta’, based on the similarity between the shape of the Nile delta and the fourth letter of the Greek alphabet, these river-created connections between land and sea come in different shapes and sizes, causing some debate over which is the ‘largest’ in the world. The Ganges is usually cited as the winner. The Danube’s delta comes first or second in Europe, depending on how you define the continent. If Europe includes south east Russia, then the Volga’s delta on the Caspian Sea takes first prize.

It’s hard to get a handle on the Danube Delta. Using Wikipedia as a source (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Danube_Delta) the overall area is 5,165 km2. In comparison, Cambridgeshire is a mere 3,389 km2. Most, but not all of those 5,000 km2 lie within Romania. And here’s the rub: some of it is in Ukraine.

Under UNESCO’s ‘Man and Biosphere Programme’, the Danube Delta was designated as a World Biosphere Reserve (WBR) in 1979 and enlarged in 1992. In 1998 it was extended into Ukraine, thus creating a significant (in biosphere terms) but more tricky (in governance terms) Transborder Reserve. If you click on the UNESCO web links to the Danube Delta WBR you get the following message: “We can’t connect to the server”. We do wonder if this is a sign of the current political situation rather than just a technical fault. Our guide for our Delta trip told us how useful drones had become in surveying the wetland ecology but that, nowadays, they can’t be used in case the drones are mistaken for missiles. The term ‘Transborder’ in this area is not just about bureaucracy.

Our guide also told us of an exciting ‘transborder’ Delta ‘Rewilding Europe’ Project (https://rewildingeurope.com/rew-project/danube-delta-rewilding-area/). Three countries are involved in this scheme: Romania, Moldova and, of course, Ukraine. Their website includes the following: “With your donation, we will be able to purchase and transfer medicine, equipment and any other priority item to cover the needs of staff, employees and their families in Ukraine.” Sadly, ecosystem support must now include the human animal as well.

We entered the world of the Delta at the port town of Tulcea which now tranships tourists as well as shipping containers. Loaded onto our tiny craft, enveloped in life jackets, we felt very small and vulnerable as we chugged along past commercial vessels which themselves were insignificant in comparison to most ocean going freighters.

Thankfully, the myriad of delta channels allows rapid reductions in scale and we were soon happily watching out for pelicans and white tailed eagles, with no vessel much bigger than ourselves in view. In that journey alone, we saw more eagles than we had ever seen before over a whole lifetime. Just the one species, mind you.

Our destination was Mila 23, once a significant location on one of the shipping routes from Tulcea to the Black Sea, and located at the 23 nautical mile marker out from the port. Today, this settlement is bypassed by commercial shipping, but has adapted well to tourism. Ourselves and our luggage were safely transferred from boat, to dock, and on into a comfortable, generously sized, family run guest house. We’ll sneak a peak in a subsequent blog.

One of us was wondering whether the delta landscape could keep us engaged and happy for the best part of four days. Team Terroir went on every available excursion, however, and never regretted a moment, even in the cold and rain. Huge thanks are due to our extremely knowledgeable guide who had left a probably much more lucrative career as a lawyer to engage full time in the conservation and interpretation of this extraordinary piece of world ‘biosphere’.

The bird life is spectacular, of course. The conjunction of water and land will always provide a richness of habitat for both flora and fauna but this extensive area of slow flowing delta, with many channels of varying depth and width, is particularly magical, especially with a knowledgeable guide with sharp eyesight and good ear for bird song.

Pelicans are the initial show stoppers. They are easy to spot, of course, being striking in their size (and this includes their feet), their idiosyncratic bills, their ability to look like flying mushrooms when surfing the thermals, and their ability to cooperate with other species such as cormorants (above right). The collective nouns which we humans have applied (squadron, pod, pouch and scoop) go some way to describe their life style.

Eventually, our bird count reached well over 40 species, including many familiar faces such as swallows, grey herons, mute swans, black headed gulls and greylag geese (right). Many, such as whiskered terns, some glossy ibis and a bearded tit refused to be caught on camera, but a few (below) were coaxed into posing for the camera.

Images above and right © Brett Halliday

This somewhat hasty shot of a cuckoo was particularly special to a crew of British tourists who, these days, seldom hear the once iconic song of an English summer. This individual cooed to us for several hours as we toured the delta waterways.

Its not just birds of course. Fish, amphibians, invertebrates of all sorts, reptiles and mammals abound but are harder to see and even harder to photograph. Some amphibians were very noisy, however, and these little critters (below left) were very active during our springtime visit. The North American muskrat was introduced to Europe in the early 20th century and is no stranger to the Danube delta. The native otter has had a harder struggle but seems to be spreading after a programme of re-introduction. We think the chap below right is a muskrat but would be happy to be corrected.

The more terrestrial landscape is also worth a look, although harder to see from water level. At first glance the water’s edge seems to be a flexible, undulating, but remarkably dense barrier of Common Reed (Phragmites australis) although it grows to such proportions that you can’t help worrying that Giant Reed (a hugely invasive pest in much of Europe) has started to colonise.

A quick web search hinted that the Giant Reed might have already been found in the Ukrainian part of the delta. Can anyone update us?

This giant reed threat is just one example of the changeable relationship between open water and land habitats. The economics of water transport has altered hugely with the introduction of aspects such as containerisation and the need for larger ocean-going vessels. Dredging and creation of more direct routes to the sea have not only meant that places like Mila 23 are now bypassed by commercial shipping, but more significantly, meant a drop in the delta’s water levels and increased colonisation by woody species. The tree is the enemy!

Let’s take a look back and see how the humans adapted to enable existence in this wetland ecosystem. Reed was the mainstay for the traditional delta communities and was used for fodder, fuel, thatch, fencing, construction and decorative purposes. Increased urbanisation and industrialisation means that demand for this crop is now severely reduced but, as we will see, some traditional management practices die hard!

We were curious about the number of burnt trees along the channel edges (see above) and were told that it was a tradition from former times. Reed and any sneaky tree species were burned to maximise the reed crop to provide its most appropriate age and size for whatever end product was required. We were told that tree burning still occurs despite the current low demand for the reed. There was a distinct impression that burning continues (see above) as an attractive pass time for the younger (males?) in the local communities!

Today, the wetland delta habitat presents a variety of ecological niches. It is a network of open water, of wide and narrow channels, of varying depths, of varying accessibility (especially if you don’t have a boat!), of varying uses and varying options according to the varying weather and varying seasons.

Water chestnut, yellow water lily and blue lotus (left to right above) love the shallows. Below, small boats love the myriad of creeks and open water bodies, which guaranteed we never really know where we were! Thankfully, our guide always knew where to look for something special, and how to get us home.

Our journey to the Danube Delta (and there will be more about this trip in our next blog) owes special thanks to some special people: Brett Halliday for allowing us to share some of his spectacular photographs; to Ramona and Dan at MyRomania (https://myromania.ro/) who can craft pretty much any type of trip to Romania, and to the people at Ffestiniog Travel (https://www.ffestiniogtravel.com/) who commissioned this particular visit. Thank you.